The Roaring Twenties are known as the Jazz Age, the time of jazz, gin, and flappers. But, less obviously, sports also played a big part in the shaping of the decade. The twenties’ love of sports is beautifully conveyed in Sports et divertissements, a rare avant-garde publication that pairs twenty musical compositions by Erik Satie with pochoir illustrations by Charles Martin, hand-coloured by Jules Saude. The Royal Ontario Museum’s Library & Archives recently acquired number 107, out of only 225 produced copies (Sherman). Published by Lucien Vogel in 1923, the magazine takes the reader on various chic excursions, from sailboats to lush picnics in the park, to my two favourites: the tennis court and the golf course. Both of these sports made a significant impact on fashion in the 1920s. “In the years following the First World War, participation in sport and leisure activities – most often tennis, golf, swimming, or sunbathing – became popular and fashionable among women of the upper classes” (Pyper). The women depicted in Sports et divertissements are no exception.

“Le Golf” depicts a woman holding a golf club, with a man with his back turned. The fetching blonde is clearly the star in Martin’s eyes. The pair dressed in their best golf whites, and matching white hats, although her much wider brim sports a pink ribbon, while his features a purple-brown one. She has white wrist length gloves with matching pink bows. The short sleeves of her dress have treble clef musical signs as the embellishment. Most surprising is the shallow v-cut neckline that reveals the shapes of her breasts, and fabric so thin that we can see the outline of a nipple. Golf is sexy; Martin must have thought. This sassy blonde is there to get some birdies, and some male attention while at it. As for Satie, his composition does not exactly correspond to the image. It reads: “The colonel is dressed in “Scotch Tweed” of a violent green. He will be victorious. His ‘caddy’ follows him carrying the ‘bags’. The clouds are astonished. The ‘holes’ are all shaking. The colonel is here! Here it is that ensures the blow: his ‘club’ shatters!” We do not see a man in tweed, and if he were here, he would have probably sweated under the heat of this blissfully sunny sky. However, Satie’s lyrics pay close attention to the clothing, with the emphasis on the tweed suiting and the bags. Fashion was most likely of importance to the composer.

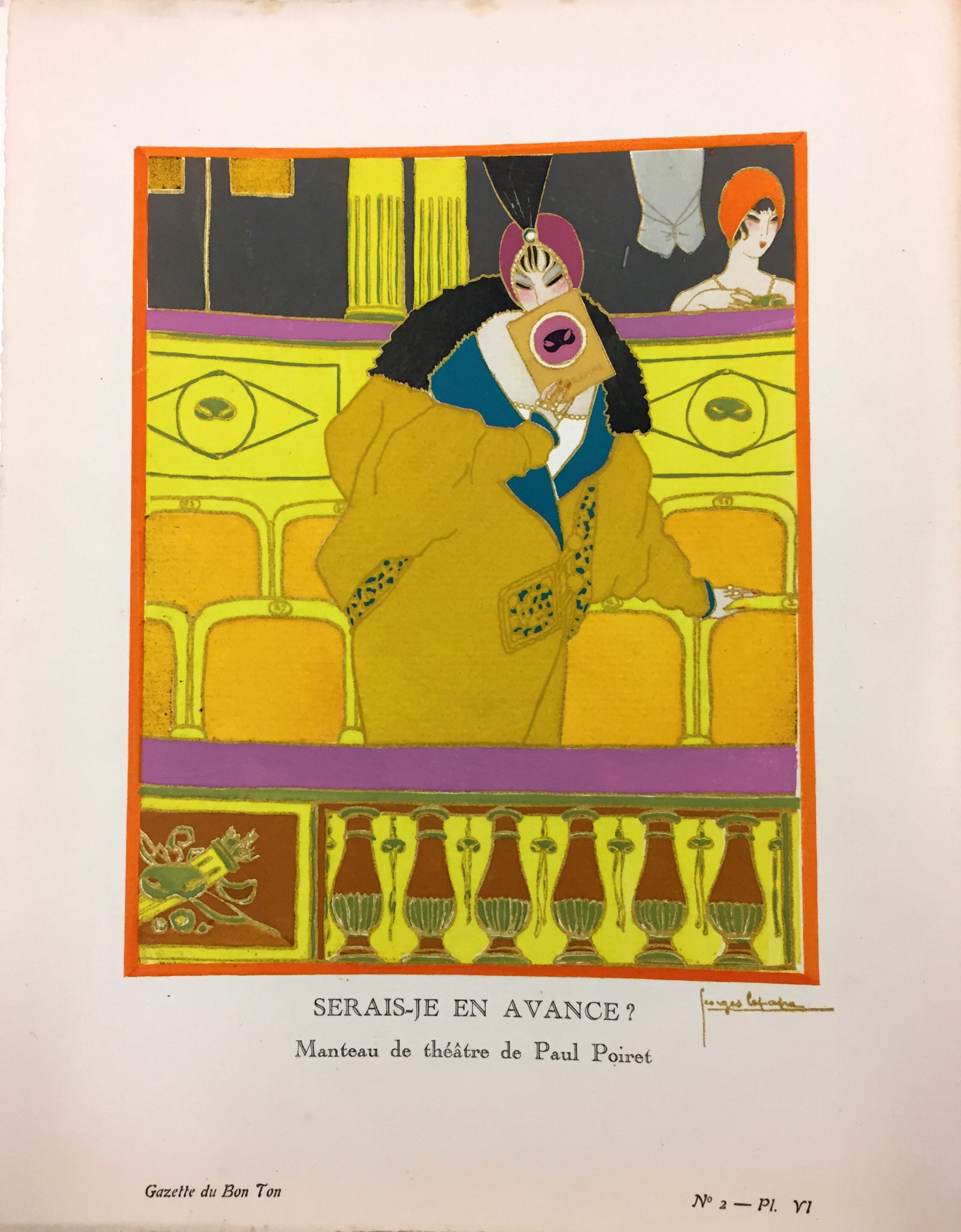

In “Le Tennis,” Satie’s lyrics read, “Play? Yes! The good server. As he has beautiful legs! He has a beautiful nose. Service cut. Game!” The corresponding illustration by Martin depicts a man and a woman whose tea service was violently interrupted by a flying tennis ball from a match happening below. The pesky ball made its way to them perhaps right after one uttered Satie’s praise of the male tennis player. He is dressed in white trousers, white short-sleeved v-neck shirt, accessorised with a black belt and what looks like a baseball hat. The stylish player is engaged in a tennis game with two women, a blonde in a pink dress and a brunette in a yellow and white ensemble. They project an image of health and sass. Our two spectators are also a stylish pair: he in a light brown fluffy, (perhaps mohair) sweater, tan trousers and two-tone black and white Oxford spectator shoes; and she in a long-sleeved sailor-inspired frock, accessorised by a thin black choker necklace. These two are members of what Veblen would have categorised as Leisure Class.

Engagement in sporting activities first came into prominence during the Victorian era, when upper-class men and women started to integrate physical activity into their daily lives. “Physical education, like related facets of material culture, became a means by which an increasingly stratified social structure (marked along the lines of class, gender, ethnicity and age) was codified and understood” (Breward, 18-19). Sporting engagement represented a certain social status, or what Veblen referred to as Leisure Class. While Veblen mostly saw sports as a frivolous activity, the focus on one’s body personified religious values of the time. Breward (19) states that “these included the concepts of ‘self-help’ and ‘self-control’, and were summoned up in the popular motto mens sana in corpore sano (‘a healthy mind in a healthy body’).” The phenomenon, whether religion or frivolity drove it, lead to growing commercialisation of sport and sporting attire. By the turn of the century, golf graced the cover of popular women’s publications such as The Ladies’ World (renamed later as The Woman’s World).

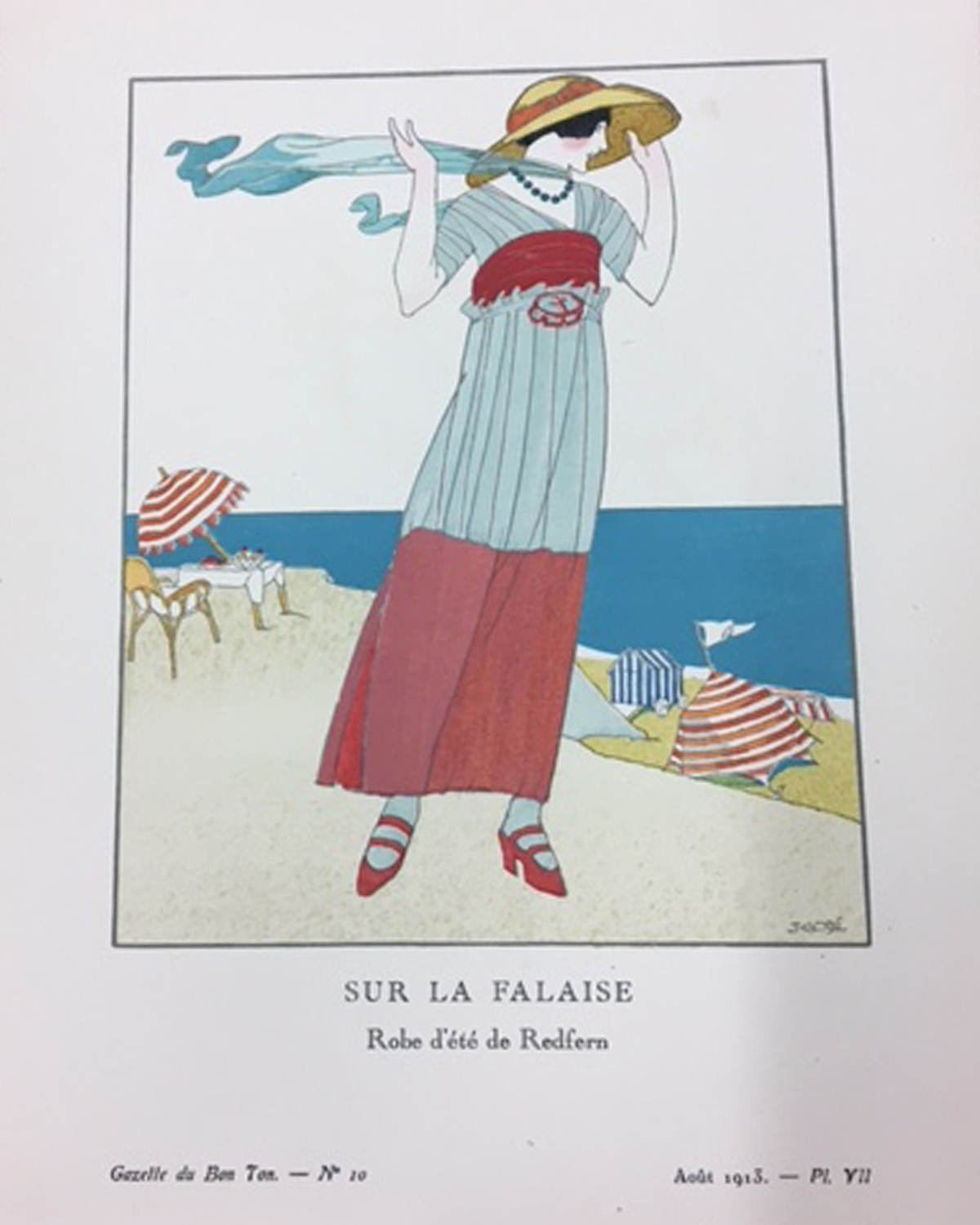

In the 1920s, sportswear had found itself into daytime wardrobes. “Between 1925 and 1928, the difference between sport and day wear seems to be in name only, as styles and fabrics for both spheres converged” (Pyper). Tennis had appeared on the cover of American Vogue in October 1921 and again in July 1922. The 1921 cover has a dreamlike quality, with a woman in a luxuriously ruffled dress floating under a starry sky. She is getting ready to hit a shooting star with her tennis racquet. On the other hand, the 1922 cover depicts two women in the midst of conversation while resting with their racquets in hand. They are dressed in long, narrow-cut frocks, perhaps not ideal for the game of tennis. The woman in white sports a red and white striped overcoat, while the woman in orange has a plush purple scarf. It is difficult to decipher if these clothes are meant for tennis or tea.

Golf also made its way into Vogue. “Fashion: The Golf Clubs at “La Bouille” and “Saint Cloud” are Smart Places for Sports and for Sports Costume” reads a September 1921 headline. The accompanying editorial illustrations depict willowy men and women congregating around the idyllic golfing grounds, engaged in all kind of profound conversation. No one is actually playing the game, but a golf club was a place to be seen. There is perhaps no better confirmation of that statement than the character of professional golfer Jordan Baker in the iconic 1925 Fitzgerald novel, The Great Gatsby. Jordan is described as a 1920s ideal of beauty and an object of affection for the story’s narrator, Nick Carraway. “I enjoyed looking at her. She was a slender, small-breasted girl, with an erect carriage which she accentuated by throwing her body at the shoulders like a young cadet” (11). Nick enjoys the status associated with the sport. “At first I was flattered to go places with her, because she was a golf champion, and everyone knew her name.” (57) Aside from golfing, Jordan enjoys ample leisure time.

Fitzgerald worked on the novel while residing in the chic French Riviera, at the time a playground of the rich and famous, according to Pyper. “Even women who appeared to have no interest in sporting pursuits began to dress in this manner while on holiday, conforming to the new craze for physical culture and the simplified silhouettes that accompanied it” (Pyper). The French used to term sportive to describe the clothing and the women who wore it. One of the designers who embraced this look was Coco Chanel. The designer had famously integrated jersey into her collections, fabric that allowed for simpler construction techniques and the ease of movement. In 1924, Chanel designed costumes for Ballets Russes’s production of Le Train Bleu, an avant-garde ballet featuring a cast in golf and tennis gear, as well as swimwear (Breward, 27).

While it may be a common interest nowadays, active lifestyle was part of the avant-garde echelon. It certainly inspired someone like Satie to pen Sports et divertissements. Completed in 1914, the composer’s twenty piano pieces were shelved for almost a decade due to World War I. When they were published together with Martin’s marvellous illustrations, they were largely ignored by critics and the general public but were revered by fellow musicians and connoisseurs (Davis, 432). Today, however, they are considered some of the composer’s best works. Satie scholar Alan M. Gillmor considered them “purest examples of the composer’s peculiar genius, revealing in abundance the endearing qualities that have become virtually synonymous with his name: wit, parody, irony, fantasy” (2). The publication was in many ways ahead of its time. Sports et divertissements pair fashion, visual art, language, and music before it was common to do so. The publication perfectly captures the decade of excess and optimism, and a time when sport was a stylish affair, perhaps more than any fashion publication possibly could have.

Works Cited

Breward, Christopher. “Pure Gesture: Reflections on the Histories of Sport and Fashion.” Fashion V Sport, edited by Ligaya Salazar. V&A Publishing. 2008. pp. 17-29.

Davis, Mary E. “Modernity à La Mode: Popular Culture and Avant-Gardism in Erik Satie’s Sports Et Divertissements.” Musical Quarterly, vol. 83, no. 3, 1999, pp. 430.

“Fashion: The Golf Clubs at “La Bouille” and “Saint Cloud” are Smart Places for Sports and for Sports Costume.” Vogue, vol. 58, no. 6, Sep 15, 1921, pp. 78, ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/904310105?accountid=1361.

Fitzgerald, F. S. The Great Gatsby. Scribner, 1953.

Gillmor, Alan M. “Musico-Poetic Form in Satie’s “Humoristic” Piano Suites (1913-14).”Canadian University Music Review, vol. 8, no. 8, 1987, pp. 1-44.

Pyper, Jaclyn. Style Sportive: Fashion, Sport and Modernity in France, 1923-1930, Apparence(s) [Online], 7 | 2017, Online since 01 June 2017, Connection on 19 March 2018. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/apparences/1361

Satie, Erik. Sports et divertissement. Dessins de Ch. Martin. Gravés sur cuivres et rehaussés de pochoir par Jules Saudé. Paris: Publications Lucien Vogel, [1923]. Print. Royal Ontario Museum Library & Archives. Rare Oversize M25 S27 S7 1923. ROM copy is numbered 159.

Sherman, Ketzia. Sports et divertissements: a unique resource for researchers in design history [Web log post]. 2017, January 27. Retrieved from https://www.rom.on.ca/en/blog/sports-et-divertissements-a-unique-resource-for-researchers-in-design-history

Veblen, Thorstein, 1857-1929. The Theory of the Leisure Class; an Economic Study of Institutions., United States, 1924.