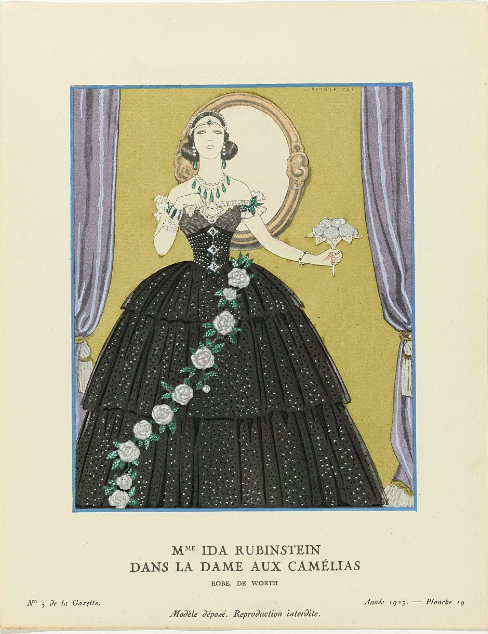

I chose to examine an image from a 1923 edition of the Gazette Du Bon Ton (hereafter referred to as Gazette). The central image is of a woman wearing an elaborate black dress, standing in front of a yellow wall and a round mirror, framed on either side by blue curtains. The woman is holding a bouquet, and flowers trail down the front of her gown. The image is captioned: “Mme Ida Rubinstein dans la Dame Aux Camelias, Robe de Worth”.

As the caption indicates, this is an illustration of Ida Rubinstein. Rubinstein was a Russian dancer and actress, active between 1908 and 1939, so the publication of this illustration falls almost perfectly in the middle of her career (Woolf, 9). She was born in 1883, and so would have been 40 at the time of this illustration; by today’s standards, she was quite old for a dancer. In the 1980s, 40 was the average retirement age for a professional ballerina, and by the 1990s the average age of retirement had dropped to 29 (“Ballet by Numbers”).

The caption also informs the viewer that this is an image of Rubinstein ‘dans La Dame Aux Camelias’, or, ‘in The Lady of the Camellias’. La Dame Aux Camelias is a ballet based on a novel by Alexandre Dumas, which tells the story of a romance that is based upon Dumas’ own life. The novel tells the story of a man named Armand Duvas who falls in love with a dying courtesan named Marguerite Gautier. Gautier signals her availability to client with camellia flowers; she wears a red flower when she is menstruating, and therefore unavailable to her lovers, while white camellias show that she is available (Dumas).

Rubinstein played the role of Gautier in a mid-1920s production of La Dame Aux Camelias, and this illustration in Gazette appears to be of Rubinstein in performance costume. The caption clues us into this, but we can also use Barthes’ theory of semiotics to read the other cues present in the illustration that reinforce the performance aspect. The curtains on either side, while not being the traditionally theatrical red, imply that Rubinstein is occupying a stage. She is wearing multiple pieces of elaborate jewelry in addition to the highly embellished gown, which we can read in several ways, depending on how much background knowledge we have of Rubinstein. She inherited massive wealth from her parents early on in life – knowing this, we may simply read the jewelry as a sign of her significant amounts of economic capital. However, if we approach the image without this prior knowledge, one may instead read the jewelry as ‘costume jewelry’, adding to the theatrics of the scene.

Since Gazette du Bon Ton primarily featured couture or couture-inspired designs, the gown Rubinstein is wearing is quite clearly not a performance costume (especially due to the length) (Davis, 56). However, the inclusion of tulle in the skirt may have been a way to give the gown a more balletic feel. The flowers trailing down the front of the gown and held in a bouquet by Rubinstein are another visual cue. These are camellias, intended to reference to the white camellias worn by Gautier in the context of the plot to signal her availability to suitors. The full, voluminous skirt and off-shoulder bodice are consistent with the style of gowns worn in the mid-nineteenth century (Dumas’ novel was published in 1848 and the ballet was first performed in 1852).

The life of Ida Rubinstein is an interesting example of intersections of capital, particularly as they were described by Pierre Bourdieu. As mentioned previously, Rubinstein inherited a significant amount of money from her parents after their deaths, endowing her with significant economic capital. Bourdieu claims that economic capital underlies all other forms, and Rubinstein’s life makes a strong argument for this. After her parents died, the very young Ida (two years old at the time) was raised by her aunt, Madame Horowitz, a “fashionable and cultivated woman” in St. Petersburg (Woolf, 3). This aunt was very well-connected, and the family mingled with the highest members of Russian society; however, this came at the price of their Jewish faith, which they ceased to practice in the face of significant anti-semitism in Russia at the time. One could argue that in this case, social (and, to an extent, cultural) capital was gained at the expense of their existing cultural capital, which came from their religious history. Interestingly, Ida’s full name, Lydia, means ‘the cultured one’ within its Greek origins (Woolf, 4). Growing up, Ida was endowed with many visible, immediately obvious forms of cultural capital (fitting with Bourdieu’s traditional vision): she was given a rigorous education and learned to speak five languages with a reasonable degree of fluency, and she was both well-mannered and beautiful. This allowed her a great deal of success within her aunt’s high-profile social circle, contributing to the family’s overall social capital.

Rubinstein’s career also invites discussion about cultural capital; particularly, how one can acquire it, and how ‘valid’ those methods of acquisition may be. When she began to gravitate towards a career in the theatre arts, Ida risked squandering much of the good grace her aunt has worked to give her; as Vicki Woolf explains, “whilst it was quite acceptable to lionize, patronize, and be entertained by theatricals, it was most definitely not acceptable to become a member of the theatrical profession itself” (Woolf, 6). Luckily for her, Ida’s aunt did not expect a career in the arts to appeal to her niece, and had her tutored in dancing, singing, and drama by some of the best teachers of their respective fields. As long as she was simply learning, and not performing for an audience, this was considered to be a method by which to accrue more cultural capital rather than lose it by damaging one’s reputation.

I do not have space to devote to describing the rise of Rubinstein’s career in full detail, but she did go on to become a prolific dancer, despite her well-to-do family’s protestations. She eventually settled into a position with the Ballet Russes and danced with Nijinsky. However, her first balletic performances were in Sophocles’ Antigone and Oscar Wilde’s Salome. What is important to note about these two productions is that Rubinstein, who was not an exceptionally talented dancer despite her high-end training, paid for and put them on herself so that she would be able to perform in the starring role. This creates an interesting intersection of economic and cultural capital, particularly if we consider theatre arts in the context of today’s values, as some of the more current writings about Rubinstein do.

Today, a prima ballerina would be considered to have significant cultural capital due to her rigorous training and the long history of the art that precedes her. Viewed through this lens, Rubinstein’s efforts to occupy that position by essentially ‘buying’ the roles is viewed as somewhat disingenuous. Take, for instance, the language used in the abstract for Patricia Vertinsky’s article Ida Rubinstein: Dancing Decadence and “The Art of the Beautiful Pose”, which positions Rubinstein against her more ‘sophisticated’ audience:

“Virtually untrained as a dancer, but mistress of the seductive gesture learned from the West (but honed in the East), Rubinstein knew just how to capture the Western eye, and she spent a fortune playing to it. The luxury of extreme wealth certainly helped open the doors to her artistic fame, and she was fortunate to be included in the sensational triumphs of the Ballets Russes as it was received by a sophisticated and enthusiastic Parisian audience.”

Rubinstein would go on to also star in productions that she did not finance, such as Cleopatre, Scheherazade, Le Martyre de St Sebastien, and Le Dame aux Camelias. She was able to achieve this success because French audiences were quite taken with her long-limbed form, even if she had muddied her good name somewhat in Russia. France’s enthusiasm for Rubinstein’s looks also explains her presence in a slightly elitist publication like Gazette du Bon Ton, where she is pictured in costume, but not in motion.

When I selected this picture from the stacks of Gazette du Bon Ton, I was simply taken with the gown and the colour scheme. I did not expect to unpack such an engaging character and so much history from it. These magazines are such an interesting window into what was really ‘fashionable’ in this era of France, and I’m curious as to what other historical characters may emerge if I were to continue looking into them.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

References

“Ballet by Numbers.” The Telegraph, Telegraph Media Group, 29 June 2009, www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/theatre/dance/5686620/Ballet-by-numbers.html.

Bourdieu, Pierre. “The Forms of Capital,” In J. Richardson (Ed.) Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education

Davis, Mary E. Classic Chic Music, Fashion, and Modernism. University of California Press, 2014.

Dumas, Alexandre. La Dame Aux Camelias. Translated by David Coward, Oxford University Press, 1986.

Jobling, Paul. “Roland Barthes: Semiology and the Rhetorical Codes of Fashion.” Thinking through Fashion, edited by Agnes Rocamora and Anneke Smelik, pp. 132–148.

Skinner, Cornelia Otis. Madame Sarah. Houghton Mifflin, 1967.

Vertinsky, Patricia. “Ida Rubinstein: Dancing Decadence and ‘The Art of the Beautiful Pose’.” Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues, no. 26, 2014, pp. 122–136., doi:10.2979/nashim.26.122.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

For Discussion:

Are there some signs present in this illustration that could use some more discussion? For instance, I was intrigued by the expression on her face and the handkerchief she is holding, but found some trouble unpacking them semiotically myself.

Wow! I seriously loved your post. I was engaged with the beautiful dress, further engaged by the Russian subject and Ballet Russe, but I am so impressed with how well you integrated the different forms of capital! You were able to discuss the subject and the capital forms extremely well, and I felt I gained an appreciation of the theory that I didn’t have before. You balanced the fashion plate, historical context, and theory perfectly. For lack of a better term, reading your post was quite the journey!

I’m curious whether she is wearing a “vintage” 1800s gown by Charles Worth himself or a 1920s interpretation by his sons of a 1800s Charles Worth gown. It actually looks quite a bit like the gown he designed for the Austrian Empress Sissi in 1865, except that Ida’s was black as opposed to white.

http://2.bp.blogspot.com/_mb6hU_h-MnE/Sypupi7nfnI/AAAAAAAACwQ/kPGpxrfZzMs/s1600-h/389px-Empress_Elisabeth_of_Austria_with_diamond_stars_on_her_hair.jpg

I enjoyed your exposé on Ida Rubinstein. She seemed like a lady that was more famous for being famous than due to her achievements – perhaps a great prototype for some of today’s celebrities, especially the so-called style icons. Although I have to admit, she looked really convincing playing the role of a prima ballerina/diva, I would have probably completely bought into her story.

You’re right, the gowns are very similar! That’s a really interesting connection. I think it would be more likely that she’s wearing a 1920s interpretation, but given the size of her fashion collection, it could very well be vintage.

I loved learning about lovely Ida. The expression on her face is intriguing and drew me in to know more about her. I don’t really know the significance but she gave me the impressions of a glamourous undead-character, like Morticia Addams 😛 Perhaps the black dress, dark hair and strange ghost-like expression was a way to play up her exoticism? She seems to have the same pale goth-vibes in the 1917 portrait – her sense of fashion was ahead of the times.