“What does it mean to be a man?” This was one of the articles featured in the premiere edition of Gentry magazine in the winter of 1951 (Gentry 73). Gentry was a hallmark gentlemen’s magazine of the 1950s and arguably ever since. Not only did it cover a wide variety of topics such as fashion, art, culture, food, home improvement, and automobiles, it did so in luxe manner with heavyweight paper, beautiful design, thoughtful literature, and samples of fabric or even spices attached to its advertisements. Gentry was “for those people who have never relished the banal or the ordinary” (Gentry 43). Gentry magazine was the ultimate gentlemen’s magazine for the ultimate gentlemen of the 1950s.

Since Gentry was a gentlemen’s “lifestyle” magazine and not solely based on fashion, the article “What does it mean to be a man?” captured its targeted reader by focusing on the broad picture of masculinity in the post-war era. The ten page exposé was rooted in literary thought, citing writers such as Chaucer and ideas of masculinity based upon Renaissance models of humanism. Undoubtedly, man was viewed as a high performance machine yet also have high levels of intellect. The article read: “A man should strive to have constant control over his body, his feelings, and his mind. Many of us have developed one part of ourselves and have neglected other parts, instead of striving to achieve a harmonious balance.” (Gentry 80-81). Male readers are challenged through the article to self-reflect on themselves as men but also simply as humans. While one might be quick to assume that an article on this topic from 1951 might be filled with ideals of hegemonic masculinity such as being able to fix a car, have an attractive wife, work your way up the corporate ladder, etc.; the argument instead mirrors a system of development similar to Maslow’s “Hierarchy of Needs” leading to self-actualization. The article ends by stating: “To the extent that he cultivates his higher nature, to that extent can he fulfill his being on earth, and to that extent is he entitled to be called a Man.” (Gentry 82).

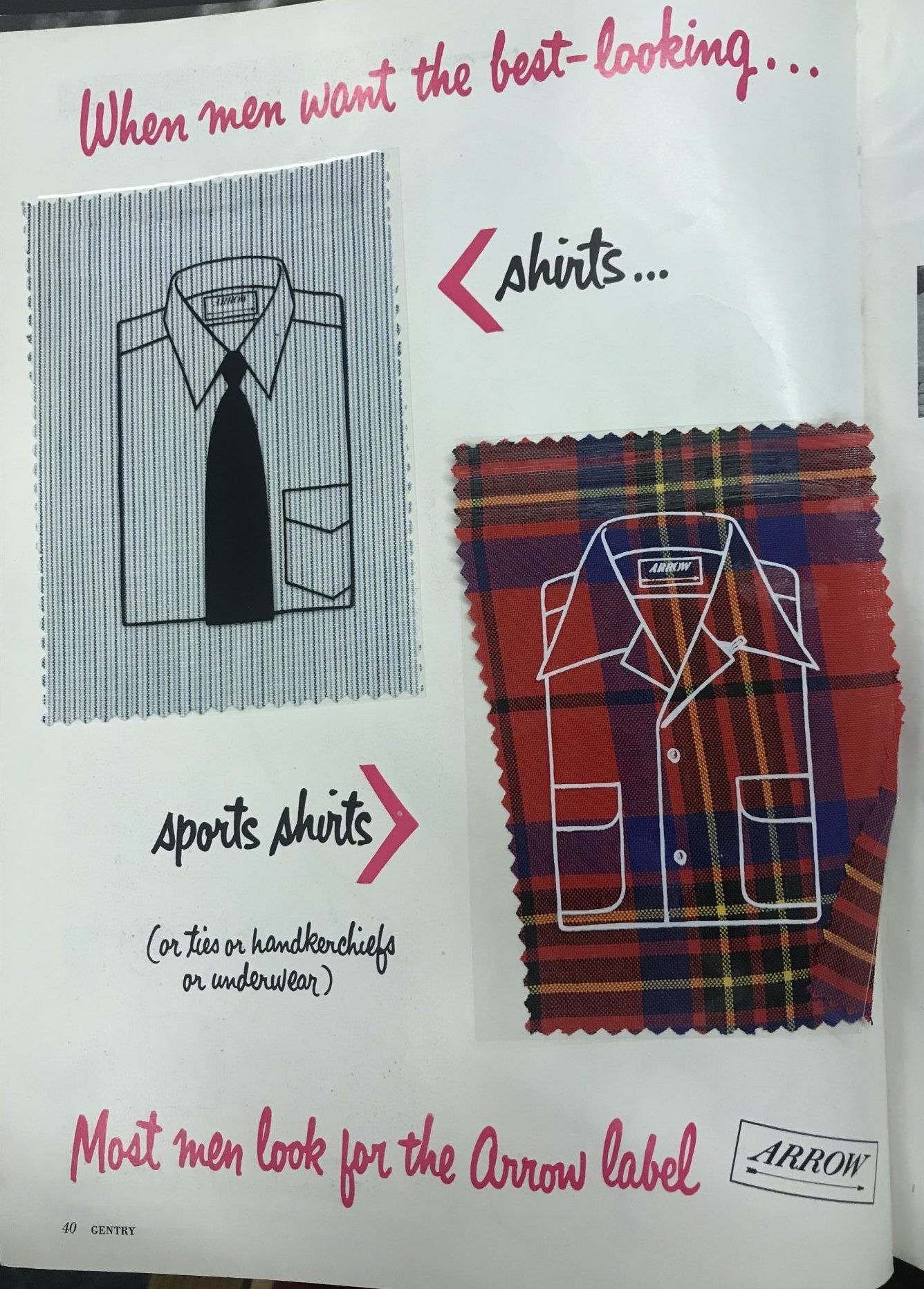

The Gentry magazine attempted to craft a mid-century version of a “Renaissance Man” who was adept at a wide variety of skills and more importantly who had wide-ranging knowledge (Bryant 20) or as Bourdieu would term “cultural capital” (Bourdieu 243). One of the areas where men were able to refine their life was through their fashion. Like most popular magazines, it was filled with of advertisements at the beginning of the copy. These included a wide variety of gifts and gadgets for the elite male, but a large portion were the latest fashions. What made Gentry unprecedented was that with most of its fashion advertisements it included real fabric swatches (Bryant 24). For time when nearly every working man was wearing a dress shirt of similar design, one of the major differences among men’s shirts was the quality and colour of the fabric making these swatches a great marketing strategy. It also gives the most accurate representation of the colours, which is unparalleled in a mainly black and white publication. In an example of an “Arrow” shirting advertisement, it is clear that the emphasis is not even on the shirt (Gentry 40). The emphasis is on the company, not the product. Arrow has a full page advertisement with two larger than average swatches. It could be assumed then that men reading this magazine knew what an “Arrow” dress shirt looked like or frankly what a dress shirt in general looked like. Fabric samples were used to differentiate levels of quality and also fashion. While the cut or style of an Arrow dress shirt might not change from year to year, the fabric, colour, and pattern might. These fabric swatches would unfortunately be short-lived and featured in only the first ten issues of the magazine before the United States Post Office (USPO) would prohibit them (Bryant 22).

In addition to fashion advertisements, Gentry also included a small editorial fashion section at the end of each issue called the “Portfolio of Gentry Fashions.” In the premiere issue, this portfolio was divided into overcoats (124), sports jackets (126), town suits (128), and fabrics (130). Unlike highly produced fashion shoots evident in contemporary male lifestyle magazines, Gentry included early “streetstyle” photographs of seemingly average men wearing each style and its variations. Each of these men are named, and while none of them might not have achieved celebrity star status, they were all members of the elite demography that Gentry was trying to speak to. The exception obviously is the “fabrics” page, which as one can guess by this point included several luxurious fabric swatches (Gentry 130). The other three pages of “fashion” include staples of men’s wardrobes with slight nuances for the 1951 gentry man. In particular, examining the page of “overcoats,” this garment is placed within the context of post-World War II development. For example, descriptions include: “A civilian adaption of the British officer’s “short-warm” outercoat worn by S. Bryce Wing.” (Gentry 128)

The overcoat is an interesting subject and title of a recent contemporary opera (based on Nikolai Gogol’s 1842 play of the same name) produced by Canadian Stage in Toronto (co produced by Tapestry Opera and Vancouver Opera) (Canadian Stage). Morris Panych’s The Overcoat: A Musical Tailoring follows a man, Akakiy, as he struggles to make ends meet in his life until he replaces his tattered coat with a majestic new overcoat. In the first act while he wore rags, his boss did not even recognize him on the street. By the second act, his boss was inviting him over for a party as a result of his new investment in an overcoat. To Akakiy’s dismay, he laters loses his new overcoat in a late night street fight. Upon losing his coat, his life is essentially over and meaningless. The line “A coat makes a man. A man makes a coat,” rings true for this opera (Panych). The ending scene of the opera illustrated how Akakiy (and ultimately all of us) was trapped inside this social order. Although Akakiy was extremely hard working, he was not taken seriously until he dressed in a certain manner. This is the same for the Gentry man. He needs to have a an overcoat as part of his caveat to be taken seriously in the world. An “Alligator Rainwear” advertisement in the magazine makes the claim that this jacket is “the coat you will live in.” This denotes that the jacket will become a second skin. To be someone you need to be wearing this coat because “a coat makes a man. And a man makes a coat.” as sung in The Overcoat (Panych).

Undoubtedly a strong parallel between Gentry and The Overcoat is the discussion of class and as Bourdieu theorized, it can be examined in light of his theories of capital. For Akakiy in The Overcoat, it was clear he had minimal economic capital; however he was able to cut back on the little food and heat he had to replace his ragged jacket with a magnificent new one. This transaction gave him incredible amounts of cultural capital but, more importantly, social capital (Bourdieu 243-244). Now he was not teased at work, but celebrated and noticed by his boss and females for his overcoat (a symbol of economic capital in an of itself). Once he lost that coat, all his capital went away with it. The power of a coat is a similar concept that Karl Marx fought as he wrote his seminal text, Capital. Marx was forced to wear a coat to do research in the British Museum library but at the same time needed to pawn the coat repeatedly for money (Stallybrass 185). Marx would write how we fetishize commodities such as the coat by giving it invisible power and meaning (in this case to control society) (Stallybrass 185-6).

Examining issues of class and capital with Gentry, one does not have to move far from the name itself. The term gentry denotes a man of an elite and wealthy class that owns land. According to Marsha Bryant, Gentry’s readership was based predominately on subscribers as this magazine was hard to find at local newsstands (Bryant 21). She wrote that most subscribers were referred by other subscribers via inserts in the magazine (21). This form of referral and subscription for the magazine is a clear example of requiring social capital that Bourdieu wrote about (Bourdieu 248). One essentially needed to know someone to be able to get a copy of the magazine each quarter. Prior to its launch, there was an advertisement for Gentry in the more mainstreamed New Yorker magazine trying to attract “The Top 100,000 Thinking Men in this Country” (Heller). The advertisement would continue to discuss how it was attempting to attract the most innovative thinkers. What the magazine was trying to do was spread this elite level of cultural capital (Bourdieu 244). Unlike other popular male magazines that would come in the 1950s such as Playboy or Esquire, Gentry tried to educate through thoughtful literature on why drawing is the most masculine art form or how to build a Finnish bath in one’s own home (Bryant 22).

On the surface, Gentry might appear to be a lifestyle magazine that perpetuates ideals of masculinity while promoting growing contemplation in Post-War America; however it is more than that. Its readers were educated and came from a high economic class, and that level of men demand a certain level of thinking and literature to create greater cultural capital (Bourdieu 243). Gentry was not just for any man who had money; they also had to have high levels of embodied cultural capital and the Gentry way of thinking. In comparison to a popular women’s magazine of the time, Vogue charged its readers $7.50 for an annual subscription of twenty issues (or $0.50/single issue) (Vogue 113), while Gentry charged $8 for its four issue annual subscription (or $2/single issue) (Gentry 24). Marsha Bryant included one subscribers quotation that said: “Your impeccable taste and high artistic standards combine to make Gentry the ne plus ultra of current publications.” (Bryant 19). While it provoked the thinking of these elite men of the 1950s, it also commanded how they look in their average day lives with staples such as the overcoat to make the ultimate Gentry man.

Obviously magazines have shifted from this transfer of information, thinking, or “cultural capital” like Gentry to promoting mass consumption from the 1950s to today, but is there a resurgence in magazines to give readers more than just commodities? (especially with the rise of niche magazines that are sometimes more book-like?)

Works Cited

Bourdieu, Pierre. “Forms of Capital.” Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. Greenwood, 1986, pp241-258.

Bryant, Marsha. “Gentry Modernism: Cultural Connoisseurship and Midcentury Masculinity, 1951-1957.” Popular Modernism and Its Legacies: From Pop Literature to Video Games. Scott Ortolano (ed.). Bloomsbury, 2018, pp19-44.

Canadian Stage. “The Overcoat: A Musical Tailoring.” https://www.canadianstage.com/Online/default.asp?BOparam::WScontent::loadArticle::permalink=overcoat. Accessed 05 April 2018.

Gentry. Winter 1951. Issue 1. Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum Library and Archives RB P.S Ge 260 No.1

Heller, Steven. Gentry. http://modernism101.com/products-page/art-photo/gentry-nos-1-22-a-complete-set-winter-1951-spring-1957-new-york-reporter-publications-william-c-segal-publisher/#.WsE5wWYZPde. Accessed 29 Mar 2018.

Panych, Morris and James Rolfe. The Overcoat: A Musical Tailoring. Canadian Stage with Tapestry Opera and Vancouver Opera. March 27-April 14, 2018. Bluma Appel Theatre, Toronto ON.

Stallybrass, Peter. “Marx’s Coat.” Border Fetishisms: Material Objects in Unstable Spaces. Routledge, 1998, pp183-207.

Vogue. 01 October 1951. Vol. 118. No. 6. Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum Library and Archives RB P.S. Vo 140 v.118: no.6. 1951: Oct.1.

Real fabric swatches! This is a nice touch, I wish we had this level of attention towards the reader in craft magazines. I think print magazines now are shifting towards being more than just disposable fashion guides. For example, the Gentlewoman includes reflexive pieces about life, short stories, a lot of interviews with women that stand out in a variety of fields.

I love your comment on how Gentry view man as a “high performance machine”. Sometimes we forget men also have great expectations on how to behave, appear in public, and so on. Could we say Gentry was a kind of specific niche magazine? I’m wondering to what extent the readers would actually follow the advice on their pages. It would be so interesting to see a very elegant, well mannered, intellectual man taking the swatch page of the magazine to his tailor and asking for a suit using that fabric.

Parker, I really enjoyed how you didn’t focus only on one image, but rather talked about several parts of the magazine, giving the reader a wider understanding of why this was published, how they approached things, who was the target market and what was being presented in it.

I think that your final paragraph was very important in order to grasp the true meaning behind everything you were presenting and what the magazine was about. As you said, it may look like just a lifestyle magazine, but there are layers and complexity behind it, and I think that you focused on these layers on your analysis, giving more value to the magazine with each new layer you unfolded.

When I finished reading it, I thought about how you touched on how the readers would be challenged to reflect about themselves and what it meant to be a person and a man. This was a beautiful way of analysing it and once again I think that you touched on the layers that the magazine had, as it was more than one would consider it to be.

Hi Parker! You did a great job unpacking the various layers to this fascinating men’s lifestyle magazine from the 1950s and relating it to Bourdieu’s forms of capital. As soon as I started reading your blog the first thing that came to mind was that the male reader of Gentry certainly needs cultural capital (to know about Gentry) and economic capital (to buy Gentry) and social capital as well. I was fascinated to learn that most readers needed to know a Gentry subscriber to be referred to acquire a copy of the magazine.

It was very interesting to learn more about a men’s lifestyle magazine from the 1950s that championed the procurement of greater cultural capital.

What a fantastic magazine that had so many unique features. Real fabric swatches! Removable colour plates! Samples of marjoram! It was a great marketing strategy then and I would be curious to know if the inclusion of fabric swatches would work effectively in today’s fashion publications.