In 1998, the television network HBO introduced a character that would become paramount to the way American women experienced shoes in the twenty-first century (1) : Carrie Bradshaw. Main character of the iconic show Sex and The City, Carrie Bradshaw is a journalist with a love for (very expensive) designer shoes. Bradshaw’s shoes (mostly Manolo Blahniks) become the fifth character (2) of the show, building narratives and making statements. For example, in season six, Bradshaw is shoe-shamed for buying Manolo Blahnik at $485, to which she responds with her theory on “a woman’s right to shoes.” Bradshaw justifies her love for luxurious footwear by saying it makes life more fun : “The fact is, sometimes it’s hard to walk in a single woman’s shoes, that’s why we need really special ones now and then…to make the walk a little more fun.” Bradshaw’s love for shoes (3) seems to reflect a common Western relationship to footwear. In the United States alone, over $8,000,000,000 is spent annually on high-fashion footwear.(4) Yet, worshipping shoes isn’t a contemporary invention.

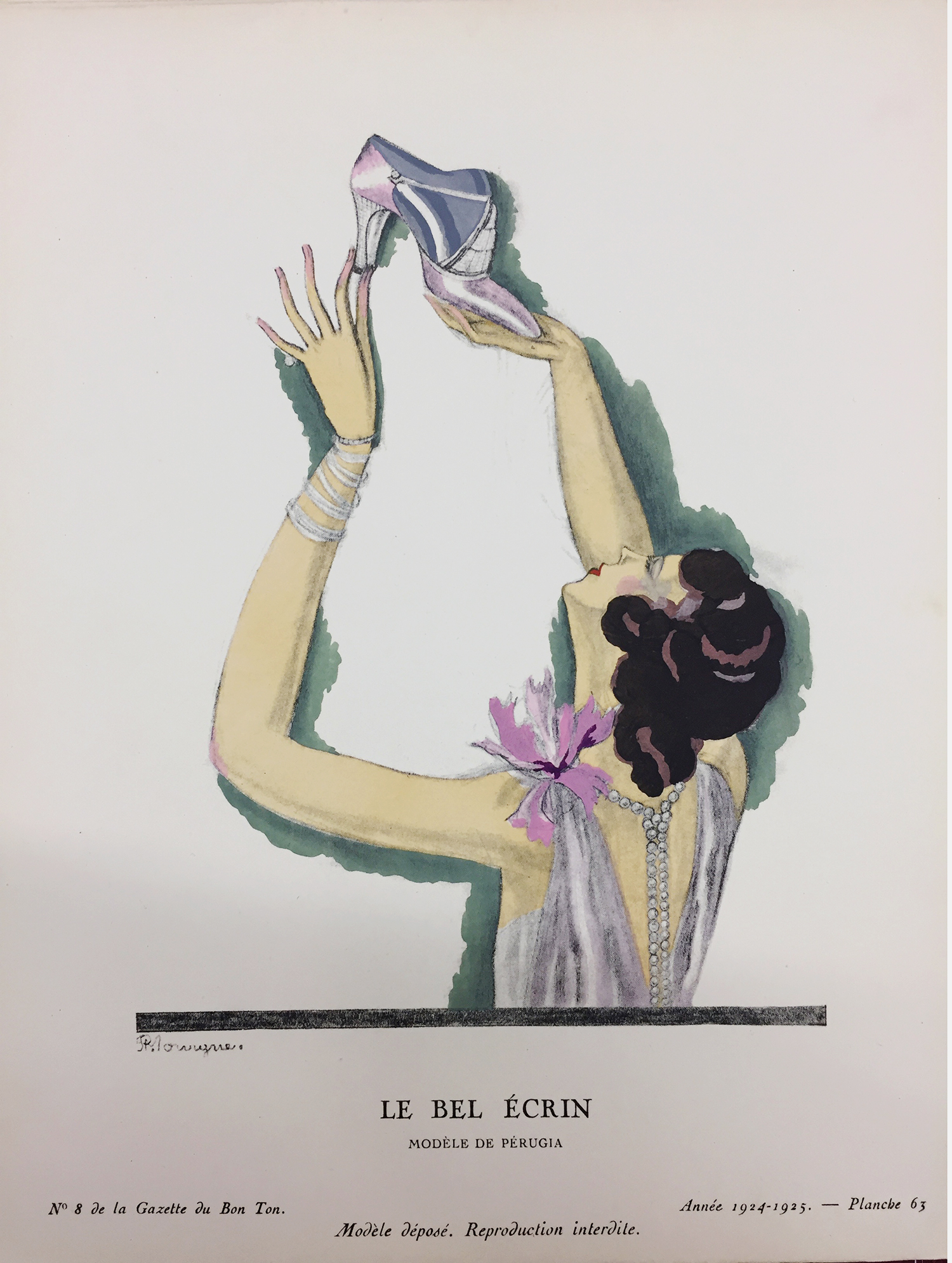

The eighth volume of the 1924-1925 French fashion journal Gazette du Bon Ton : Art, Modes & Chronique, published a fashion plate by artist Pierre Mourgue in which the shoe is stealing the spotlight from the woman. Indeed, the woman is turning her back on the viewer, focusing her attention on the shoe, directing the viewer’s gaze directly to the accessory. Not only does the shoe becomes the center of attention because of the woman’s gaze on it, but its position, up in the air, above the model, and in the center, can suggest a certain importance, becoming almost superior to the human. Moreover, the woman is scrutinizing the shoe as if it were a precious gem, reinforcing the superior status of the accessory.

When considering Roland Barthes’ semiological theory, closely examining this fashion plate (and the fashion it represents) may reveal a certain meaning. (5) Indeed, when examining the signifier (the fashion plate) in relation to the signified (the cultural context it was produced in), a meaning could arise (the sign). Because Barthes prioritizes text over visual elements(6), the semiological analysis first needs to consider the information offered through captions. In this case, the caption reveals that the silver and lilac high heeled shoe (which is the exact same colour as the dress) displayed is a model by André Pérugia. Pérugia was an important shoe designer in the first half of the twentieth century.(7) More importantly, the title “Le Bel Écrin” reinforces the position of the shoe as a luxurious possession. Indeed, “écrin” is the French word for a jewellery case box, suggesting that the shoe is a case for the precious foot. This emphasis on the shoe, and therefore on the foot, could be related to the birth of psychoanalysis that happened at the end of the nineteenth century and that was very popular with surrealist artists of the period. Indeed, in various writings, Sigmund Freud emphasized the symbolism of the feet, granting this bodily part with a high status. (8) When considering this caption and the way the woman is admiring the shoe, we can conclude that the journal compares the feet to jewelry and the shoe to a precious jewelry box. Therefore, both the composition and the caption reinforces the shoe’s status as a mythical, worshiped object.

Indeed, this fashion plate doesn’t depict the shoe as a simple tool to protect the feet when walking, but as a luxurious product, protecting the jewelry-like feet. This depiction can be understood in regards to the context and fashion trends of the period. In the 1920s, shoes and stockings became the focus of attention in fashion trends.(9) Indeed, the decade’s fashion evolved around higher hemlines, waistless dresses and short hair. For the first time in centuries, women were showing their legs in public and, as a result, their shoes were completely visible.(10) Marie-Agnès Parmentier argues that the flappers’ fashion “further entrenched the association between heels and seduction.”(11) Indeed, flappers’ garments were very controversial (12) and heels had for centuries been associated with sexuality. For example, Valérie Laforge suggests that in Ancient Rome, prostitutes were recognized from other women by the height of their heels.(13) Similarly, in the middle of the nineteenth century, “high heels became infused with erotic significance” (14) as the concepts of courtesans and sexuality became important topics in Europe. Edouard Manet’s Olympia (1863) is a good example of how high heeled shoes “were emerging as a standard accessory to the commodified body.” (15) Similarly, in the 1920s, flappers suggested their sexual availability through their high heels, short dresses and makeup. Elizabeth Semmelhack argues that 1920s women suggestively displayed their legs in response to the lack of marriageable men. (16) Indeed, both the First World War and the Spanish flu had greatly decimated the population and it became difficult to find husbands. (17) Considering the context, it therefore makes sense to position the shoe as the focal point of this illustration, since footwear was an important element of women’s fashion.

However, high heels were not just associated with flappers’ sexuality. (18) Indeed, high heels, and shoes in general, hold various meanings, and have done so for centuries. (19) Through history, the shoes have often taken various mythical positions. For example, shoes were found in tombs from Roman Empire, suggesting a belief that footwear held magical power. Indeed, “they were there to ensure that the deceased walked in splendour in the otherworld.” (20) Similarly, in Ancient Egypt, platform shoes were associated with wealth and power. (21)

The popularity of the high heel would even have arisen from the fact that they made the feet look smaller by hiding parts of them under the skirts, leaving only the toes visible. (22) Indeed, small feet were symbols of natural nobility, a symbol that can be read in the late seventeenth century edition of Charles Perrault’s Cinderella. (23) The Cinderella fairytale also suggests that shoes hold a mysterious transformative power, which can change a woman’s life. This narrative can easily be related to the context of the 1920s. Indeed, as mentioned previously, some scholars argue that the flappers used shoes as a way to attract men…the same way Cinderella finds her prince through the glass slipper. As a result, Cinderella’s narrative could be easily related to this fashion plate, since the elevated position of the shoe suggests a certain power. This power could have been linked to the fact that showing elegant high heels for the flappers was a way to openly show their open sexuality as a way find a husband. Moreover, Cinderella elevates her social position through her shoes (24), the same way wearing beautiful shoes in 1920s could help to elevate a woman through marriage. Indeed, Helen Persson argues that “our choice in shoes can help project a fully realized image of who we want to be.” (25) Charles Perreault published the first European version of Cinderella in France in 1697, we can therefore consider that the artist was aware of this transformative association with shoes.

Moreover, when the Gazette du Bon Ton published this fashion plate in 1925, the magazine would have been sponsored by the most important couturiers in Paris, such as Worth, Paquin and Poiret, and was geared towards an elite readership. (26) Indeed, the high end fashion journal used the technique of the pochoir, a “laborious and expensive process” (27) and high quality paper and print, which made it quite expensive. According to Linda Kathryn Pilgrim, artists were commissioned to draw couture pieces, but they didn’t just copy the garments : they created narratives. In this case, the shoe’s position seem make reference to the mythical and transformative power of footwear and especially of high heels. Because the magazine was commissioned by haute couture designers, we could suggest that this fashion plate was composed specifically as a way to justify the prices and quality of haute couture pieces by comparing the shoe to a jewelry. Indeed, we can assume that designers financing the magazine would have encouraged placing haute couture in a mythical, luxurious position. It was a common practice for those couturiers to market their creations as works of art as a way to encourage purchases and to reinforce their value and authenticity. (28) Considering that the shoe designer Perugia worked privately with Poiret (29), this fashion plate was used as a marketing tool.

However, because whenever the signifier or the signified change, the sign is automatically modified too, (30) this analysis can’t completely establish what this illustration meant in a 1920s context. Indeed, we can try to understand how this fashion plate translated into a sign in its context of creation, yet the signified can’t be the same because my cultural background won’t ever be the same as a 1924-1925 elite woman who was the target audience for this illustration. As a result, because Barthes’ theory is defined and applied through subjectivity, the previous analysis can’t be completely objective. Yet, interestingly, the mythical position of the shoe is still relevant in a twenty-first century Western context. Indeed, as mentioned in the introduction, shoes still hold a very important mythical position in our society. Why do shoes specifically play such important roles? Considering how shoes “can dictate the wearer moves” (31) by affecting the posture and the way one walks, is it possible to study shoes only visually, without considering the wearer’s embodied experience? Indeed, Persson argues that shoes are more difficult to sell at auction houses such as Christie’s than selling haute couture garments because they are so closely connected with the bodies that wore them. (32) Considering that shoes aren’t investment pieces like designers’ handbags are, what makes people so attracted to them? Persson argues that “we simply love shoes,” (33) do you agree?

_________________________________________________________________________

End Notes

(1)“Of course, the desire for shoes, and for certain maker’s shoes, is not new, but Carrie Bradshaw ensured that these brands became a part of a cultural vernacular. Owning a pair of Manolos became aspirational: you would not just acquire a pair of expensive shoes, but you would live the dream of a glamorous, extravagant lifestyle, like that of pampered celebrities.” Helen Persson, “Objects of Desire : The Cult of Shoes,” in Shoes : Pleasure and Pain, ed. Helen Persson (London: V&A Publishing, 2015), 21.

(2) Kim Akass and Janet McCabe, Reading Sex and the City, (London: I.B. Tauris, 2004), 137.

(3) Akass and McCabe,Reading Sex and the City, 166.

(4)Lewis, David M. G. Lewis et al., “Why Women Wear High Heels: Evolution, Lumbar Curvature, and Attractiveness,” Frontiers in Psychology 8, (2017) : 1

(5) “Semiology, therefore, propounds the very persuasive idea that everything is a text that can be decoded as a sign and, moreover, that the signified object is not like a single word, but rather a sentence in its own right.” Paul Jobling, “Roland Barthes : Semiology and the Rhetorical Codes of Fashion,” in Thinking Through Fashion : A Guide to Key Theorists, ed. Agnès Rocamora and Anneke Smelik, (London : I.B. Tauris, 2016), 136.

(6) Jobling, “Roland Barthes,” 138.

(7) Klaus Carl and Marie-Josephe Bossan, Shoes, (New York : Parkstone Press International, 2011), 198-200.

(8) Joseph Fernando, “Foot Symbolism,” Canadian Journal of Psychoanalysis 6, no. 2 (1998): 309-320.

(9) Christina Probert, Shoes in Vogue since 1910, (New York : Abreville Press, 1981), 18.

(10) “During the 1920s, the flapper-style dress, which was based on a loose tunic or tubular shift, dared to reveal more of the female leg than ever before in modern Western history.” Myra Walker,”Miniskirt,” in The Berg Companion to Fashion, ed. Valerie Steele, (Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010), 513.

(11) Marie-Agnès Parmentier, “High Heels,” Consumption Markets & Culture 19, no. 6 (2016): 514.

(12) Sauro “Flappers,” 339.

(13) Valérie Laforge, Talons et tentations (Quebec : Fides, 2001), 58-59.

(14) Elizabeth Semmelhack, “A Delicate Balance : Women, Power and High Heels,” in Shoes : A History from Sandals to Sneakers, eds. Giorgio Riello and Peter McNeil, (Oxford : Berg, 2006), 230.

(15) Semmelhack, “A Delicate Balance,” 230.

(16) Elizabeth Semmelhack, Heights of Fashion: A History of the Elevated Shoe, (Pittsburgh : Periscope Publishing, 2008), 38.

(17) Semmelhack, Heights of Fashion, 38.

(18) Clare Sauro “Flappers,” in The Berg Companion to Fashion, ed. Valerie Steele, 339-341, (Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010), 339.

(19) Semmelhack, “A Delicate Balance,” 224.

(20) Colin McDowell, Shoes : Fashion and Fantasy, (New York : Rizzoli, 1989), 60.

(21) Laforge, Talons et tentations, 52.

(22) Semmelhack, “A Delicate Balance,” 227.

(23) Semmelhack, “A Delicate Balance,” 227.

(24) McDowell, Shoes : Fashion and Fantasy, 61.

(25) Persson, “Objects of Desire : The Cult of Shoes,” 17.

(26) Linda Kathryn Pilgrim, ““La Gazette Du Bon Ton: Arts, Modes, and Frivolités”: An Analysis of Fashion and Modernity through the Lens of a French Journal De Luxe” (master’s Thesis, University of Southern California, 1999), 5.

(27) Pilgrim, “”La Gazette Du Bon Ton,” 1.

(28) Nancy J. Troy, “Poiret”s Modernism and the Logic of Fashion,” in The Fashion History Reader : Global Perspectives, eds. Giorgio Riello and Peter McNeil (New York : Routledge, 2010), 455.

(29) Carl and Bossan, Shoes, 198.

(30) “These two entities are indivisible in the sign itself. Thus, if the signifier is changed, then so too is the signified and, by implication, the sign.” Jobling, “Roland Barthes,” 135.

(31) Persson, “Objects of Desire : The Cult of Shoes,” 17.

(32) “Persson, “Objects of Desire : The Cult of Shoes,” 21.

(33) Persson, “Objects of Desire : The Cult of Shoes,” 21.

_________________________________________________________________________

Bibliography

Akass, Kim and Janet McCabe. Reading Sex and the City. London: I.B. Tauris, 2004.

Carl, Klaus and Marie-Josephe Bossan. Shoes. New York : Parkstone Press International, 2011.

Esman, Aaron H. “Psychoanalysis and Surrealism: André Breton and Sigmund Freud.” Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 59, no. 1 (2011): 173-181.

Fernando, Joseph. “Foot Symbolism.” Canadian Journal of Psychoanalysis 6, no. 2 (1998): 309-320.

Jobling, Paul. “Roland Barthes : Semiology and the Rhetorical Codes of Fashion.” In Thinking Through Fashion : A Guide to Key Theorists, edited by Agnès Rocamora and Anneke Smelik, 132-148. London : I.B. Tauris, 2016.

Laforge, Valérie. Talons et tentations. Quebec : Fides, 2001.

Lewis, David M. G., Eric M. Russell, Laith Al-Shawaf, Vivian Ta, Zeynep Senveli, William Ickes and David M. Buss. “Why Women Wear High Heels: Evolution, Lumbar Curvature, and Attractiveness.” Frontiers in Psychology 8, (2017) : 1-7.

McDowell, Colin. Shoes : Fashion and Fantasy. New York : Rizzoli, 1989.

Oria, Beatriz. Talking Dirty on Sex and the City: Romance, Intimacy, Friendship. Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield, 2014.

Parmentier, Marie-Agnès. “High Heels.” Consumption Markets & Culture 19, no. 6 (2016): 511-519.

Persson, Helen. “Objects of Desire : The Cult of Shoes.” In Shoes : Pleasure and Pain, edited by Helen Persson, 10-21. London: V&A Publishing, 2015.

Pilgrim, Linda Kathryn. ““La Gazette Du Bon Ton: Arts, Modes, and Frivolités”: An Analysis of Fashion and Modernity through the Lens of a French Journal De Luxe.” Master’s Thesis, University of Southern California, 1999. ProQuest (1409654)

Probert, Christina. Shoes in Vogue since 1910. New York : Abreville Press, 1981.

Sauro, Clare. “Flappers.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele, 339-341. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. https://www-bloomsburyfashioncentral-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/products/berg-fashion-library/encyclopedia/the-berg-companion-to-fashion/flappers.

Semmelhack, Elizabeth. “A Delicate Balance : Women, Power and High Heels.” In Shoes : A History from Sandals to Sneakers, edited by Giorgio Riello and Peter McNeil, 224-245. Oxford : Berg, 2006.

Semmelhack, Elizabeth. Heights of Fashion: A History of the Elevated Shoe. Pittsburgh : Periscope Publishing, 2008.

Troy, Nancy J. “Poiret”s Modernism and the Logic of Fashion.” In The Fashion History Reader : Global Perspectives, edited by Giorgio Riello and Peter McNeil, 455-465. New York : Routledge, 2010.

Walker, Myra. “Miniskirt.” In The Berg Companion to Fashion, edited by Valerie Steele, 513-514. Oxford: Bloomsbury Academic, 2010. https://www-bloomsburyfashioncentral-com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/products/berg-fashion-library/encyclopedia/the-berg-companion-to-fashion/miniskirt.

I love the parallel that you did with pop culture icon Carrie Bradshaw. It gives a great contemporary example to address the stereotypes around the relationship of women and luxury footwear. I found the use of Barthes semiotic approach to deconstruct the meaning associated with the shoe in the illustration very relevant and useful to position this object in time. I also really appreciated that you mentioned the attention paid to the composition of this image, as I find that a lot of illustrations from that period were stronger in terms of representing clear and strong messages despite the lack of technology. Perhaps the case of Sarah Jessica Parker’s character would be equally interesting to analyze following Barthes approach

I really enjoyed this post! I thought you successfully covered the many areas that shoes are associated with – such as pop culture, embodied experience, theory – and had great analysis in each area. I also appreciate how you’ve brought so much new information, analysis, and viewpoints to a topic I’ve seen you talk about before (your Colour Theory presentation on red shoes in popular culture. This was a great accompaniment to that presentation). Most of all, I really like your discussion question which ties together the whole post. To discuss the attractiveness of shoes and their investment value, I think it really depends on the style of shoe (ie heels or sneakers), and how much they’re worn, and by who. I’m somewhat aware of sneaker culture and ‘sneakerheads’ who put so much care into making sure that if they do wear their limited edition or iconic shoes that they do not damage them. At the same time, this past autumn there was an auction at Christie’s for personal objects that belonged to Audrey Hepburn, and many of her shoes (almost all ballet flats, size 9) were a very popular item to bid on (perhaps because they were more affordable), despite being plain and obviously worn. I think the value in the former is placed in its craftmanship and status symbol, whereas the latter has value in its ”life” belonging to an iconic celebrity. When it comes to shoes known for their artistry, like Mr. Blahnik’s creations, I think their best second life is to be in a museum to be admired by all, because I really don’t think people could afford second-hand luxury shoes would feel comfortable wearing them, that it’s somehow unsafe and highly damaging to the shoe. And as you said, shoes are so personal to the wearer – which is where who they belonged to can make such a difference in their value. The common thread between these three categories I’ve highlighted is that the basis is a love of shoes (clearly Audrey loved a certain style of shoe) that elevates the object to have a mythical power. The knowledge of possessing a certain style of shoe or a shoe that belonged to a certain person makes the shoe special, even if it’s never worn.

Lauriane, Did you read my former MA student Hilary Davidson’s essay on the magic of red shoes in Peter McNeil and Giorgio Riello’s Shoes book?

Just curious!

Yes, I did. For our colour class, we had to do a mini-conference, and I did mine of red shoes. So her essay was actually an important part of my research!

amazing, thanks! 🙂

I just wanted to say that I really enjoyed this comment about the post! Lauriane, you did a great job on your post, making it a very pleasant read, and Emily brought points that I also thought about, like the value attributed to things based on craftsmanship and also symbolic value. 🙂

Love this post! This is incredibly insightful. I appreciate the ties between more modern pop culture references to shoes as a fetish object and to narratives like Cinderella and the glass slipper.

I wonder if this could be extended a bit into mentioning more of Bordieu and luxury. The idea of the heel not only as a signifier of sexuality but of luxury, and specific heels like Jimmy Choo heels or Manolo Blahnik heels are indicative of a very specific class bracket. I think Marx might have some input too given that often these shoes are valued for much more beyond the crafting of a shoe, and speak to the magical power that these fetishized commodities hold.

I think this is an amazing interpretation though and I really love the print it’s almost funny in a way, because of how she is reaching up to this divine shoe.

As soon as I saw the word “shoes” in the title, I knew I was going to love this post. What impressed me even more was your seamless integration of research and pop culture examples. I really enjoyed the Carrie Bradshaw reference. In terms of iconic fashion duos, Carrie and Manolo Blahnik are right up there. I searched online, and found this amazing Vanity Fair article that highlights significant moments of their ‘relationship’ from the show Sex and the City (posting here, just for fun): https://www.vanityfair.com/style/2015/09/a-complete-gif-history-of-carrie-bradshaw-and-manolo-blahnik

For Carrie, Manolos are more than “just shoes”–and no doubt, because they are certainly not the price of your average heels from Aldo, and even those can be expensive sometimes. Like the Gazette du Bon Ton fashion plate you analyze, Manolos are like jewellery boxes for Carrie’s feet, making her travels as a single woman “a little more fun.” What is interesting is that this changes in the first Sex and the City movie, when Big proposes to Carrie with a pair of blue silk Manolo Blahnik pumps instead of a traditional diamond ring; in this case, the shoe is the jewel, just like Cinderella’s glass slipper is, as you mention. This example demonstrates how even shoes can carry different meanings. Their significance varies depending on when we wear them, and what our experience is in that moment. As items that we wear on our feet, they literally represent different walks of life, and that, I think, is partly what makes shoes so alluring.