It is surprising that a magazine from one hundred and six years ago still preserves its print qualities as if it had been produced recently (fig. 1). La Gazette du Bon Ton first issue dates from November 1912 but the one analyzed here is the second issue from December 1912 and is part of the Royal Ontario Museum’s collection (v. 1, no. 2). What draws attention to this particular magazine is the treatment of content and illustrations. La Gazette du Bon Ton is the product of Lucien Vogel’s mind. An art-director turned editor-in-chief (Davis 49), Vogel was inspired by the quality of Le Journal des Dames et des Modes, the last publication that valued “high standards of production”. Le Journal ceased to be printed when its publisher passed away, opening space for “cheaply produced journalism for mass circulation” (Lepape and Defert 69). In that current state of low-quality publication, the Gazette aimed to elevate fashion to the condition of art, giving to it the same prestige as painting, sculpture and drawing enjoyed in the early years of the twentieth century. The magazine as media also had to be treated as a work of art. The Gazette’s first edition declared “[w]hen fashion becomes an art, a fashion gazette must itself become an arts magazine” (Lepape and Defert 72). Fashion at the time was “not simply reflecting social change, it was also undergoing an internal stylistic revolution” (Steele 208). On its pages, La Gazette was pairing artists and couturiers in a pursuit to present readers a way of life rooted in good taste and elegance with a touch of humour (Davis 49).

And indeed La Gazette du Bon Ton emanates an artisanal feel due to its small size, pages with rough edges that appear to have been ripped from a larger sheet. The paper is coarse and textured, appropriate for painting and for the pochoir technique and the pages are stack together rather than bound, adding an extra touch of sophistication; its fashion plates could be, therefore, framed as little pictures (Lepape and Defert 69). The illustrations on fashion plates, signed by the illustrator/artist contrast with those used in the editorial pages. They are more elaborate, presenting different drawing styles depending on the artist’s style. The layout throughout is designed with large margins all around, copy or illustration is located in the centre of the page, there is a consistent matching colour palette, and the typography is clean and easy to read. Each spread is carefully designed to privilege blank spaces in relation to content. Drawings on style pages are accurate representations of the accessories and clothes suggested for use in the elaborate and quite extensive accompanying text. In one story (see fig. 2 and 3), the subject is winter sports, and the copy gives suggestions about appropriate garments to wear, how to combine them with accessories and further report about the place the reader will visit, offering travel tips.

It seems the Gazette was also relying on the social capital of its readership to reinforce its prestige as a publication that was poised to dictate good taste. Bourdieu defines social capital as “membership in a group – which provides each of its members with the backing of the collectivity-owned capital, a ‘credential’ which entitles them to credit, in the various senses of the word” (Bourdieu 248-249). Sold under a subscription-only model, La Gazette cost 100 francs per year, a significant amount of money, which positioned the publication for an audience on a higher income level (Davis 50). Established authors, or as the Gazette’s announcement proclaimed “the most brilliant reporters” (Lepape and Defert 73) wrote about topics of interest to an elite immersed in matters of art, music and high culture in general (Davis 51). Thus, as Bourdieu explains, there must be a demand of effort to maintain a social capital, “which implies expenditure of time and energy and so, directly and indirectly, of economic capital, is not profitable or even conceivable unless one invests in it a specific competence” (Bordieu 250).

Fashion plates

Fashion plates were the focus of attention at La Gazette du Bon Ton. Each issue included “ten plates coloured by the pochoir process and accompanied by captions and short articles in a witty or light-hearted vein” (Lepape and Defert 72). In the end, there was a list called “Explication des Planches” (Explanation of Plates, see fig. 4), a description of each garment presented and, for this second edition, signed by Lucien Vogel. This extra text inserted apart from the plates themselves, separates fashion from art, in a sense that garments featured could spoil their artistic rendering with language that was both essentially banal and part of the discourse typical of fashion. Bourdieu and Delsaut argue that “words that are used in fashion writing do not simply describe the value of objects they are related to, they make it” (Rocamora 239). For both Pierre Bourdieu and Roland Barthes, “fashion exists not only through clothes but also through discourses on them” as explained by Rocamora in her article, “Pierre Bourdieu: The Field of Fashion” about that author’s work. Clothing on Gazette’s plates is given a new meaning when we compare the captions of the plates with the description on the explanation list. Take for example plate Pl. IV (fig. 5): the illustration’s subtitle reads “Le Soir Tombe… – Robe de Soir de Doucet (Evening falls… Evening gown by Doucet). While, on the explanation list, there is a full description in regards to the fabrics, colours, patterns and other materials that were used to make this outfit, such as white fox fur. Both texts talk about the same garment, but in two different ways. The caption does what Barthes defined as “rhetorical code, concerning how fashion is translated into words and images in magazine spreads…his concern is with clothing as text or sign” (Jobling 134). Because this caption calls the outfit an “evening gown” it can only be understood as such while the descriptive text reinforces the sophisticated nature of the materials used to produce it, so, there is no other possible interpretation for this piece (sign), despite resembling a nightgown, for sleeping.

Is this funny?

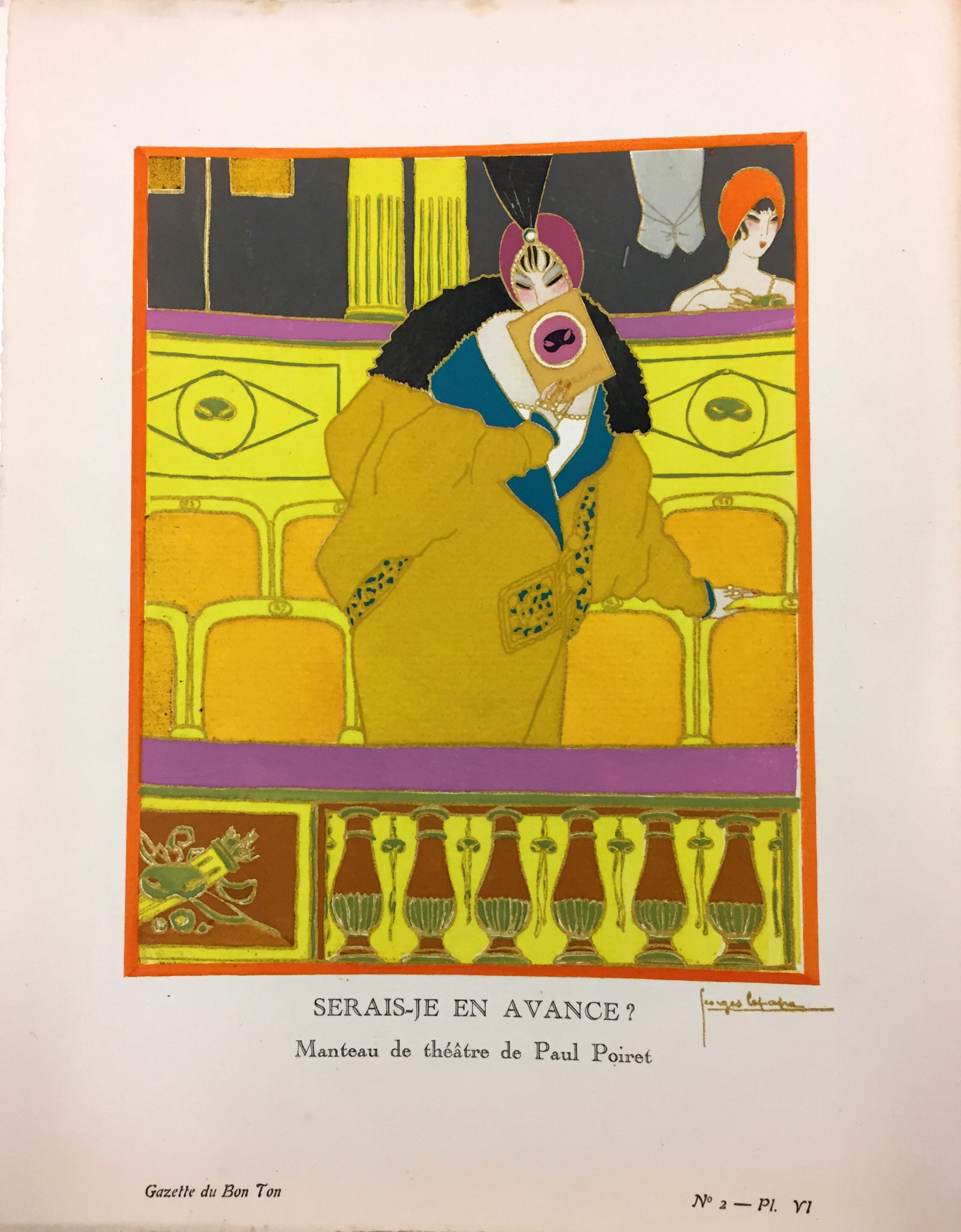

Text on fashion plates also made use of smart and humourous language, but as George Lepape defined, they were “in somewhat mocking and ironic terms” (Lepape and Defert 72). One example is the “Le Soir Tombe…” plate mentioned above and its subtle humour. Tomber in French means “to fall” but it sounds almost like tombeur which means “ladykiller”. So, in this illustration, the night falls, as does her dress, and she is ready to prey on men. Lepape was one of the artists that illustrated the pages of the Gazette and had previously contributed his work to the Salon des Humoristes (Lepape and Defert 58). One of his plates entitled “Serais-Je En Avance? – Manteau de théatre de Paul Poiret” (Pl.VI, Am I Early? – Theater Coat by Paul Poiret, see fig. 6) exemplifies the witty caption combined with a stylish drawing. The humour in this plate comes from this woman arriving early to the theatre, on purpose, to draw attention to herself and her vivid coat. The plate is also illustrated with vibrant colours that “vibrate on the page, and are matched in the fantastical depiction of the theatre itself … the scene suggests the general sensibility of the Ballets Russes and evokes with particular clarity the exotic world and stunningly aggressive colour scheme of Schéhérazade” (Davis 54). The kind of humour portrayed in this and other plates, seems restrained, to be consistent with the tastes of the Gazette’s readers. The Bon Ton, or good taste, on the Gazette’s name is in this case, “aesthetic experience … as a socially and historically constituted opposition” (Rocamora 241). Bourdieu argues, taste is a construction of the dominant class, whereby taste marks the dominant class and therefore dominant culture (Rocamora 242).

In contrast, humour in satires was far more explicit in relation to fashion and they “disdained those who dressed outside their immediate age group or, worse, those who dressed above their social station, posing an alarming threat to the social status quo” (Flood and Grant 23). Fashion satires employed exaggeration to the depictions of fashionable people (Flood and Grant 8). Distortion of body parts presents a fine line between satire, as in fig. 6, and the women illustrated on the Gazette’s fashion plates. While men were often illustrated in a fairly proportionate way (see fig. 7). It was not the magazine’s intention to mock their audience, as Davis reminds “the magazine conveyed an artistic tone and an aristocratic aura that firmly distinguished it from the ever-burgeoning ruck of fashion periodicals” (51). However, female figures were sometimes depicted in a fragile manner, often looking like they were losing balance, or with an arched back, giving a sense of instability reinforced by their small feet. In the words of art historian and Gazette’s contributor, Jean-Louis Vaudoyer (Davis 50) regarding George Lepapes’ art “[t]he type of woman created by Monsieur Lepape is not a femme fatale. He favours what our songwriters call ‘little angels’: tiny rosebud mouths, eyes round with surprise, partly tilted noses” (Lepape and Defert 76). Lepape defined his fashion illustration work as “a realistic drawing, but very stylized, bold and sumptuous, reflecting a life of elegance” (Lepape and Defert 43). This idea can also be seen in the style of other artists, not only for fashion plates but also on the renderings of garments that illustrate the stories.

The resulting portrayal of women comes close to the fashion satire and the less elegant frame La Gazette du Bon Ton so keenly tried to distance itself from. The Gazette gives us a glimpse of how high-quality fashion magazines looked like at the beginning of the twentieth century. It is an exquisite product made for an elite to read with no comparison to today’s mass circulation publications.

Discussion question

1. Are niche fashion magazines today emulating Bourdieu’s idea of discourse as a sign of differentiation and creating a hierarchy and therefore positioning themselves at a higher level in comparison to the popular ones?

Works Cited

Bourdieu, Pierre. “The Forms of Capital.” Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education. edited by J. Richardson, Greenwood, 1986, pp. 241-258.

Davis, Mary E. “La Gazette du Bon Ton”. Classic Chic: Music, Fashion, and Modernism. vol. 6, University of California Press, 2006, pp. 48-92.

Flood, Catherine, and Sarah Grant. Style and Satire: Fashion in Print, 1777-1927. V&A Publishing, 2014.

Jobling, Paul. “Roland Barthes: Semiology and the Rhetorical Codes of Fashion.” Thinking through Fashion: A Guide to Key Theorists. edited by Agnès Rocamora and Anneke Smelik, I.B. Tauris, 2016, pp. 130-148.

Lepape, Claude, and Thierry Defert. From the Ballets Russes to Vogue: The Art of Georges Lepape. Vendome Press, 1984.

Rocamora, Agnès. “Pierre Bourdieu: The Field of Fashion.” Thinking through Fashion: A Guide to Key Theorists. edited by Agnès Rocamora and Anneke Smelik, I.B. Tauris, 2016, pp. 233-250.

Steele, Valerie. Paris Fashion: A Cultural History. Bloomsbury USA, 2017.