In the beginning of the 20th century, upper-class Parisians would rely on the magazine Gazette du Bon Ton as their source of fashion trends, corroborating Barthes’ understanding of how a magazine is a generator of what is, or isn’t, in fashion (Jobling 132). As described by Oreskovich, this was an exclusive French publication, founded by Lucien Vogel, with the objective of presenting the “connections between art, fashion beauty and lifestyle” (par. 1). By focusing on these three areas, it can be inferred that Vogel believed that there was a connection between the three. It is interesting to notice that many decades after the magazine, Blumer also highlighted how fashion influences any field in which operates (276).

Seventy issues of the magazine were published from 1912 to 1925, with seven of the ten unbound prints of in each issue presenting only “the most current haute couture designs from the top Parisian fashion houses” (Oreskovich par. 2). The other three pictures, on the other hand, were creations of the illustrators, usually inspired by the trends that were being presented. In addition, all the prints in the magazine were engravings, according to museum print collections, that were coloured by hand using stencils, a process called pochoir. The annual subscription to the Gazette was 100 francs, that today would be the equivalent to $400USD (Oreskovich par.3).

With the magazine being a source of what was in fashion during a certain time, it is possible to understand this as an example of Blumer’s concept of how fashion adopts an imperative position, sanctioning what should be done and demanding adherence (276). Furthermore, since the magazine had a specific target market (upper-class Parisians), it becomes clear that it was expected that people would react to fashion’s “character of propriety and social distinction” (Blumer 277). People used the Gazette as a source that would lead them to be respected since these were styles approved by the sophisticated elite. Thus, the advertising of the clothes was converting their use value into symbolic value (Jobling 140), meaning that people should buy them because they were fashionable and were accepted by the elite.

When visiting the ROM library, I came across one of the editions of the magazine: the eight yearly Gazette du Bon Ton, from June 1913. On the cover appears the Gazette’s name, the month and year, the Issue number and the director’s name, Lucien Vogel, with the name of the editor, Emile Levy, from the Librairie Centrale des Beaux-Arts, located at 13 Rue Lafayette, in Paris. It also has a subtitle: art-modes and frivolities, that are the types of content being featured in it.

Figure 1 Vogel, Lucien. Cover of the Gazette du Bon Ton. 1913. Gazette du Bon Ton. Ed. Emile Levy. Paris, 1913. n. 8. Print. Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum Library and Archives

Figure 1 Vogel, Lucien. Cover of the Gazette du Bon Ton. 1913. Gazette du Bon Ton. Ed. Emile Levy. Paris, 1913. n. 8. Print. Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum Library and Archives

On the first page of the issue, there is a list of the seven designers that are being presented in it: Cheruit, Douillet, Doucet, Paquin, Poiret, Redfern and Worth. Underneath their names, we are made aware that these designers are collaborating with the Gazette, giving advice and reserving their first creations of every month, that will be drawn in collaboration with the newspapers’ illustrators. These seven designers had signed exclusive contracts with the magazine, so that their styles would only be shown by the Gazette (Oreskovich par.2).

Figure 2 Vogel, Lucien. List of Houses. 1913. Gazette du Bon Ton. Ed. Emile Levy. Paris, 1913. n. 8. Print. Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum Library and Archives.

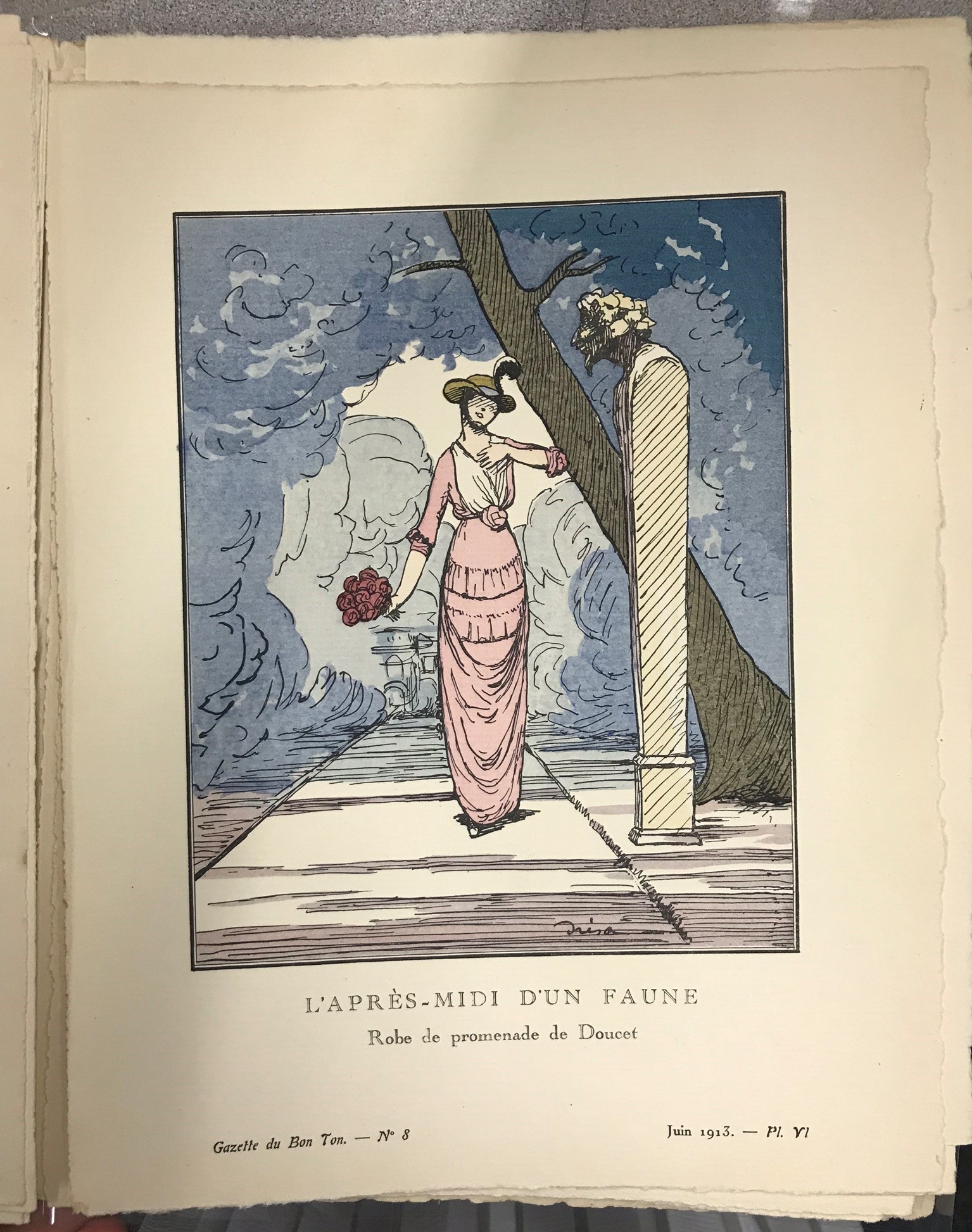

One of the beautiful prints in this specific volume is an image stenciled on a sheet measuring 19 x 24,5cm, signed by Dresa (illustrator Jacques Dresa) in the lower right. In the centre of the image, there is a woman standing in a long pink draped dress, that has three-quarter sleeves, a white collar and a flower, in the same colour as the dress, in the front. She is posing wearing a brown hat with one feather on it; she has her left hand up to her chest, a blissful expression on her face, and is holding a bouquet of red roses in her right hand. In the image, she is surrounded by trees, walking on a white pavement and is standing beside a tall statue. Underneath the image, the name of the print is written in French: l’Après-Midi d’un Faune, with the description of the garment and the name of the designer Robe de Promenade, by Doucet. On the bottom left of the print, we can read again the name of the magazine (Gazette du Bon Ton) with the number of the issue (N°8). On the right, the date (June 1913) with the number of this specific plate (VI).

Figure 3 Vogel, Lucien. L’Après-Midi d’un Faune. 1913. Gazette du Bon Ton. Ed. Emile Levy. Paris, 1913. n. 8, Plate VI. Print. Courtesy of the Royal Ontario Museum Library and Archives.

This image can be read by thinking about Barthes’ definition of fashion. In the image, we can see the rhetorical code, or in other words, how fashion is being shown through the combination of the words and the image of the woman (Jobling 134). This garment in the picture, as proposed by Barthes, is only imaginary, since it leads to the recognition of the images and not practices (134). Furthermore, by analyzing the image through a semiological approach, we can perceive that there is a signifier, the dress itself, in contact with the signified, leading to our understanding of the image as a sign (Jobling 135). It is my own understanding that at the time of the print, 1913, the more fabric one wore, the more expensive, and therefore, the richer, the person was. Thus, by knowing that this magazine was meant to be purchased by the elite, and the woman in the image is wearing a draped dress with a big amount of fabric, I read this as a sign of wealth, classiness and elite.

When I first saw this image in the Gazette du Bon Ton, I was immediately struck by memories from my childhood. I was, just like any other child, fascinated by Disney features, knowing lines and scenes by heart. By looking at this woman, I was reminded of the Grecian character named Megara, from the Hercules animation. I connected the image that I was seeing to a scene where Meg sings “I won’t say I’m in love”. As the title describes it, she denies being in love with Hercules, who has just given her a flower, making her feel vulnerable and looking at him with a loving expression. At the same time, she doesn’t want to be feeling this, leading her to the song.

Gifs created from the movie Hercules.

After researching more about the image displayed in the Gazette du Bon Ton, I used an online tool to translate the name of the dress, to learn that this was meant to be an everyday garment since Robe de Promenade translates as “walking dress”. I also translated the name of the print, l’Après-Midi d’un Faune, which would be mean “afternoon for a faun”. I found this to be very interesting since, in the Hercules movie, there is also a faun, named Philoctetes, a Greek hero that was part of the Trojan War. This similarity made me think about how the two pieces had more things in common than I would have expected at first. Only after learning the meaning of the name I saw that the statue beside her is one of a faun, whom she is looking at. It was only possible for me to perceive that the statue was a faun by thinking about Phil’s beard and then perceiving that the figure in the print had the same one.

Gif created from the movie Hercules.

I believe that the primary reason that made me think of Meg while seeing this image in the Gazette was the characters’ dress. The dress in the image was centrally positioned, in a different colour than the rest, making it stand out. I think that when seeing draped dresses, some people, including myself, would make connections with the Greeks since they are usually depicted wearing this style of garment. This use of similar styles of dress through the decades, and by different means, can be understood as the recurrence of fashion since an immediate and total recycling of fashion is to be expected (Braudrillard 88). Furthermore, Simmel’s definition of how fashion can be understood as the imitation of an example, satisfying social adaptation (543), comes to mind.

When researching to know more about this image from the Gazette, I discovered the poem with the same name, l’Après-Midi d’un Faune, written by the symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé, in 1867. According to Lloyd (154), this poem inspired the creation of musical compositions (Prélude à L’après-Midi d’un Faune by Claude Debussy) and ballets (Afternoon of a Faun by Vaslav Nijinsky, 1912, Jerome Robbins, 1953, and Tim Rushton, 2006). It is very interesting to highlight that Mallarmé used symbols to express the truth through suggestion, more than he used the narrative itself (Lloyd 187). In this sense, his notion it is closely related to the semiological understanding of things, since symbols, and therefore signs, are central to Barthes’ concepts (Jobling 132). Furthermore, it becomes clear that without the caption of the image in the Gazette du Bon Ton, I would not have discovered the purpose that the designer had imagined for the dress and the connections between this print and the work of other artists. Thus, corroborating with Barthes’ understanding of the importance of words, since captions can transmit information that may not be evident in the picture (Jobling 138). In addition, the way that Mallarmé’s poem inspired several other pieces alludes to Bourdieu’s definition of cultural capital, since the poet’s cultural goods were symbolically appropriated by others (247).

The use of the Gazette to display what was in fashion and should be worn by the elite shows us that Simmel was correct when pointing out that fashion revolves around the adoption by a social set, demanding imitation by its members (558). Furthermore, the connection between the image shown here, from 1913 and the movie Hercules from 1997, are examples of how recurrence is an integral part of fashion. In addition, it becomes clear that only by looking at one picture in a magazine, I was able to make connections with my childhood and find other links with orchestras and ballets, something that may happen whenever we see a sign.

It is known that at the time, the Gazette was closely linked to the Ballets Russes, since as proposed by Davis, there were similarities between the magazine’s “editorial agenda and the Ballets’ glamorous meshing of fashion and art” leading to the Gazette faithfully reporting on their performances (52). In this sense, it is possible to infer that maybe even when the illustrator, Jacques Dresa, was creating the narrative surrounding the Robe de Promenade, was influenced by memories of the the Ballet performance, that happened only one year before, in 1912. As proposed by Davis, the upper-class audience was intrigued by the ballets for two reasons: they rejected bourgeois values and had “femmes fatales” and “androgynous boys” as main characters (52).

After learning more about the image in the Gazette and thinking about it through the lenses of these authors here exposed, I came to think about the meaning of the narrative that was being told. I believe that my understanding of the image is biased since I connected this woman to Megara. Now, I can’t help but wonder if she had a blissful expression because she too, was in love, singing about how she had found someone. Could the flowers in her hands be given to her by a lover, just like Hercules and Meg? Was her dress, the environment and the whole narrative of the print supposed to make the reader think about love? I also wonder if the fake flower in her garment is a symbol, a reference to the real flowers in her hands, as a way of showing that they are important to the narrative. Furthermore, is the print suggesting that by wearing a couture gown by Doucet, one will find love?

There are no answers to my questions, but since I had already made a connection between the two images, this is the way that I am reading this picture. In a way, this is closely related to Barthes’ definition of post-modern hyperreality: an image based on another image, with correspondences between form and content of two different things (Jobling 140). I end my analysis of this print by thinking about how my understanding of the narrative in the print was compromised by my memories of a movie. It is important to realize that someone else could have a far different perception of the image. I inferred things and read the Gazette’s image by taking into consideration the subjectivity of perceiving a narrative in an advertising. It is to be expected that someone that first read the poem written by Mallarmé, in 1867, would have this as an influence when looking at this print from 1913.

Gifs created from the movie Hercules.

Works Cited

Baudrillard, Jean. “Fashion, or the Enchanting Spectacle of the Code.” Fashion theory: A reader, edited by Malcolm Barnard, Routledge, 2007, 462-474.

Blumer, Herbert. “Fashion: From class differentiation to collective selection.” The Sociological Quarterly vol. 10. no. 3, 1969, 275-291.

Bourdieu, Pierre . “The Forms of Capital.” Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson, Greenwood, 1986, 241-258.

Davis, Mary E. “La Gazette du Bon Ton,” Classic Chic: Music, Fashion and Modernism, Oakland: University of California Press, 2008, 48-92.

Hercules. Dir. Ron Clements and John Musker. Walt Disney Studios Motion Pictures, 1997.

Jobling, Paul. “Roland Barthes: Semiology and the Rhetorical Codes of Fashion.” Thinking Through Fashion, edited by Agnès Rocamora, I.B.Tauris, 2015, 132-148.

Lloyd, Rosemary. Mallarmé: the poet and his circle. Cornell University Press, 1999.

Oreskovihch, Julie. Gazette du Bon Ton: A Journal of Good Taste. Abe Books. https://www.abebooks.com/books/features/lithographs/Gazette-du-bon-ton.shtml. 29 March 2018.

Simmel, Georg. “Fashion.” The American Journal of Sociology, vol. 62, no. 6, 1957, 541-558.