La Gazette du Bon Ton was first published in November 1912 and was edited by Lucien Vogel (see figure 1).

Produced for 13 years until its last issue in 1925, La Gazette du Bon Ton was a fashion magazine and was used as a guidebook by affluent Parisians who adored fashion and exclusivity. La Gazette du Bon Ton was an influential “deluxe book, more than a fashion periodical” (Davis 48) and it was deemed “required reading” and “set the standard for elegance and luxury in the fashion press” (Davis 48) in order for the reader to learn more about fashion and lifestyles by feasting their eyes on the advertisements and articles, as well as the hand drawn fashion illustrations that represented art, fashion and desired lifestyles during this era. La Gazette du Bon Ton was exquisitely produced on delicate paper and its beautifully vibrant, hand illustrated, fashion plates presented up to date fashion while honouring French traditions and encouraging modernity.

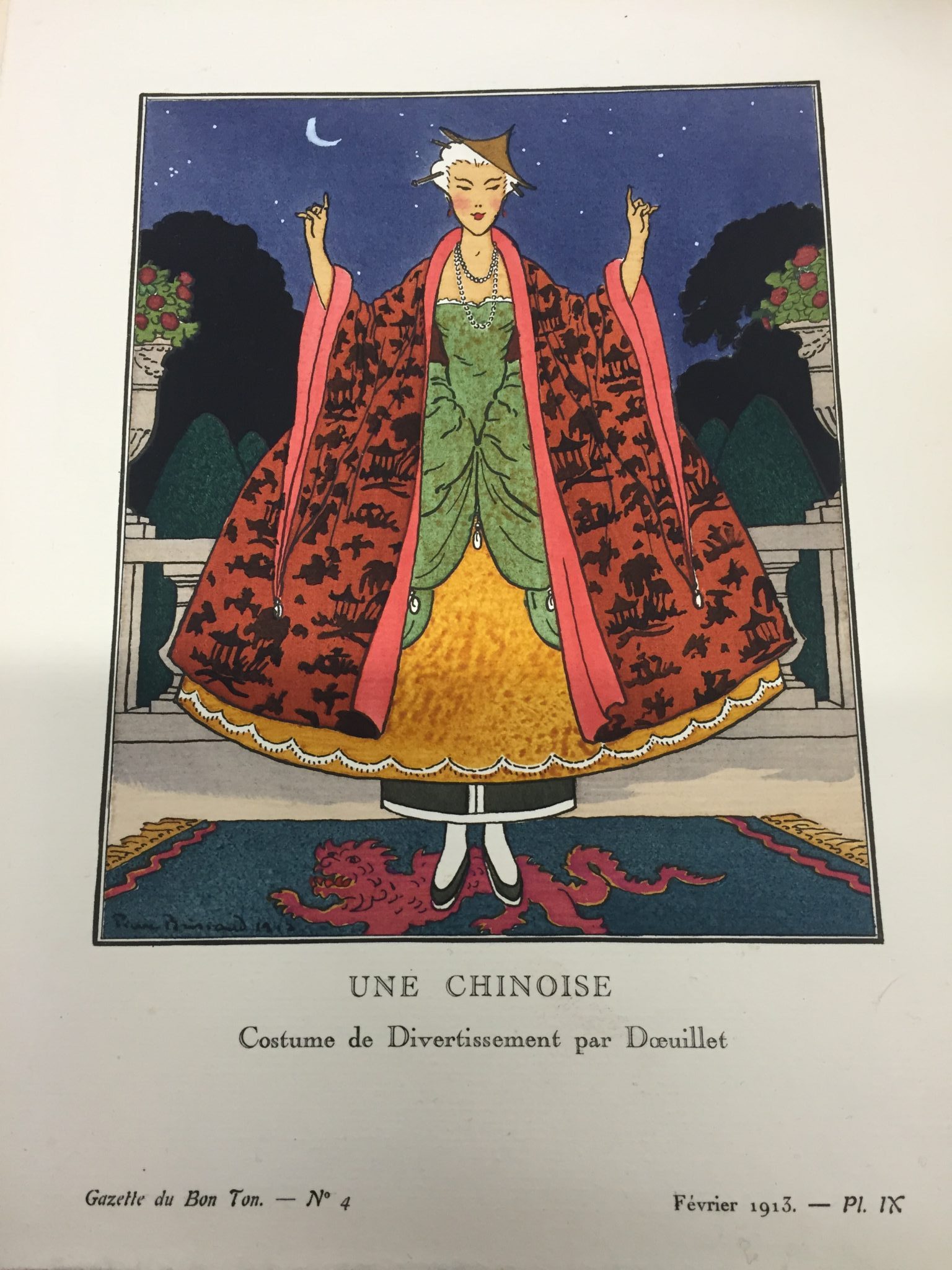

Illustrated by French painter and engraver Pierre Brissaud (1885 – 1964), “Une Chinoise: Costume de Divertissement par Douillet” was featured in La Gazette du Bon Ton’s, No.4, Pl. IX in February of 1913 (see figure 2).

Douillet received critical acclaim in various publications for his fashion designs and he increased his international popularity by licensing department stores in New York to use his designs (Percoco). Georges Douillet achieved further success in the 1910s and 1920s when his work appeared in La Gazette du Bon Ton (Percoco).

This vibrantly saturated illustration features artwork that depicts a flamboyantly dressed woman entitled “une Chinoise”. This fashion plate features a woman of an ambiguous ethnicity and according to the “explication des planches”, the model is dressed as a “Chinese” woman wearing an outfit designed by couturier Georges Douillet that features a red and black overcoat that covers a satin pannier on a silk skirt embroidered with garland trim at the hemline. In addition, the dress below the skirt is made from lightweight silk.

This illustration is problematic because it is an example of both Orientalism and cultural appropriation. Firstly, “Une Chinoise, Costume de Divertissement par Douillet” translates to “a Chinese woman in a costume for fun/entertainment by the couturier Douillet”. Orientalism is defined by the Oxford Dictionary as “the representation of Asia in a stereotyped way that is regarded as embodying a colonialist attitude” and “style, artifacts, or traits considered characteristic of the peoples and cultures of Asia”. “Une Chinoise” was drawn wearing stereotypical chopsticks in her hair and a brown, pointed, rice paddy hat tilted to one side on her head. This is an example of Orientalism and cultural appropriation because the pointed rice paddy hat is stereotypically associated with poor, hard working farmers or labourers who work outdoors in East Asian and South Asian countries. The hat is not worn for entertainment or aesthetic purposes but it is rather utilitarian. Its purpose is to protect the wearer from the rain or from the blistering sun as it radiates down onto the worker withstanding the arduous task of difficult, long hours working outdoors, or specifically in rice paddy fields (see figure 4).

In Japan, another form of this conical hat is known as jingasa (see figure 5).

During the second half of the Edo Period from 1700-1860, a jingasa was worn by Japanese warriors while they travelled, or once they had established a military camp (Popovic). In Japanese, “jin” means military and “gasa” means hat, therefore, this hat was used in the military as a means of protection and was not worn for fun nor entertainment. In China, this hat was worn by soldiers in the 1900s (see figure 6) and continues to be worn by labourers to the present day. The hat is called “dǒu lì” in Mandarin and translates to a “conical bamboo hat” in English. In Korea, a similar hat is called “satgat” and in Vietnam, this pointed hat is called “nón lá” or a leaf hat (Popovic). In Japan, another form of the jingasa is called sugegasa which is worn by labourers in Japan for protection from the sun and rain (Popovic). The sole purpose of this hat in Asia was to protect the wearer from the elements.

In the fashion illustration from 1913, Brissaud drew “une Chinoise” wearing the Asian conical hat not in a way that the hat was intended to be worn (by Asian military or by labourers who work outdoors) but rather by a wealthy, bourgeoise woman as an accessory for fun/entertainment. This is an example of both Orientalism and cultural appropriation because a person of Asian descent would not wear the rice paddy hat “for entertainment” or out of the context of working outside under the sun or in the fields, but rather as a practical way of protecting themselves from the rain or the sun while working outdoors. The illustration, “une Chinoise”, demonstrates a lack of understanding and respect to the cultures from which the hat originates.

Pierre Brissaud illustrates “une Chinoise” wearing the rice paddy hat paired with an ostentatious gown, during the evening, after the sun has set. This odd pairing illustrates that the artist is making an ignorant joke and neither respects nor understands the culture in which he is appropriating. Secondly, according to James O. Young, cultural appropriation occurs when “members of one culture (I will call them outsiders) take for their own use, items produced by a member or members of another culture (call them insiders)” (5). In addition, the Cambridge Dictionary defines cultural appropriation as “the act of taking or using things from a culture that is not your own, especially without showing that you understand or respect this culture”. Evidence of cultural appropriation is found in the chopsticks in her hair, the pointed hat, the overcoat and her hand gestures. The Oxford Dictionary also states that, “Orientalism produces non-Western cultures as unintelligible” which is evident in the way that the character is portrayed as wearing a hodgepodge of mismatched fashion and accessories. Edward W. Said posits, “…Orientalism is nothing more than a structure of lies or myths which, were the truth about them to be told, would simply blow them away” (6). This illustration is “structured by myths” because “une Chinoise” is wearing a ridiculous outfit that would not be worn in any real context. According to Edward W. Said, “Orientalism is more particularly valuable as a sign of European power over the Orient” (6) which is evident in the way that “une Chinoise” is dressed as over-the top, clownish entertainment, in comparison to other European fashion plates that show order and glamour.

According to the V&A, Chinoiserie emerged in the 17th century, became a popular style in the 18th century and its popularity continued to resonate through the 20th century. Derived from Orientalism, Chinoiserie was a European interpretation of design and art from China, Japan and other countries in Asia. Due to the rise in trade between China and East Asia, a mysteriously exotic image of Asia emerged in Europe and inspired many designers to “imitate Asian designs and to create their own fanciful versions of the East” (V&A). Moreover, the Rococo style is related to Chinoiserie in regards to fantasy, asymmetry and ornate decorations that are evident in both styles (V&A). Georges Douillet was familiar with Chinoiserie and people in Chinese clothes were the star of the Chinoiserie style, furthermore, Chinoiserie became a symbol of wealth and class. According to the V&A, “sometimes these figures were copied directly from Chinese objects, but more frequently they originated in the designer’s imagination.”

The way in which Brissaud and Douillet presented “une Chinoise” is problematic because they employed cultural appropriation in their depiction. “Une Chinoise” has an ambiguous ethnicity, is wearing a white wig, two strands of pearls around her neck, red earrings, a form fitting green bodice with a sweetheart neckline and white trim by her décolletage. The bodice cascades onto a green, silk skirt with jewelled embellishments. The 18th century gown features a green skirt that drapes over a large, satin, goldenrod yellow pannier. There is a black silk, tubular slip dress underneath the goldenrod pannier that features a white border at the hemline and two white lines down the centre paired with matching black and white flats and white socks. Worn on top of her dress is an elaborately decorated black and red overcoat that features a motif of pagodas, foliage and wildlife silhouettes. However, the red overcoat more closely resembles a banyan/kimono hybrid, which is another example of cultural appropriation.

“Une Chinoise” stands square to the viewer, in the centre of the frame while making two gestures with both her hands. This hand gesture is made by creating a fist and allowing the pinky and index finger to stick straight out, palms facing outwards, thumbs tucked in. Her hand signal resembles the “rock on” or the “devil’s horns” hand gestures that you see at rock concerts in North America. I do not think that “une Chinoise” was telling the viewer to “rock on” therefore further research illuminated the symbology of this hand gesture. Found within the freemasons’ secret society, this hand gesture represented an allegiance and exclusive membership to the occult organization (“Masonic Hand Signs Exposed”). However only freemasons knew the true symbology behind this hand signal. In Hinduism, this hand gesture is called “Apana Yogic Mudra” and it represents health and the rejuvenation of the body. It is believed that this hand gesture eliminates toxins and impurities from the body thus promoting good health (Chakraborty). In classical Indian dance, this specific hand gesture represents a lion (Charkaborty). Perhaps “une Chinoise” is making the “Apana Yogic Mudra” or a “lion” hand signal, which is another example of Orientalism and cultural appropriation. What was Brissaud’s motivation to add these hand gestures to “une Chinoise”?

Furthermore, “une Chinoise” is depicted posing at the exterior of a party, on a clear evening with stars and a crescent moon in the distance, while standing on an affluent terrace with potted, red, flowers on each side of her. She is also standing on an oriental rug that features a red dragon at the centre of it with a border of gold tassels at the edge of the rug. According to Veblen who stated, “it has in the course of economic development become the office of the woman to consume vicariously for the head of the household; and her apparel is contrived with this object in view (344)” therefore, fashion is a means of communication to represent one’s class or wealth. Evidence of this is found in the fashion, as well as the oriental rug “une Chinoise” is standing on. The oriental rug is a symbol of both Orientalism and knowledge of the outside world. Both the oriental rug and fashion were items of luxury and a symbol of wealth, power, class and conspicuous consumption. Conspicuous consumption was also evident in the white wig worn by “une Chinoise”. In the early twentieth century, wigs were also a symbol of class and wealth (“Hair Today, A History of Wigs”). During this time, a woman’s hair was regarded as her “crowning glory” and large, voluminous, white wigs styled in feminine upswept ways were on trend and in fashion during the early 1900s (“Hair Today, A History of Wigs”).

According to Bourdieu’s theory, “une Chinoise” is a person depicted to have “possession to economic capital…a taste which condemns them to like only what they can afford to like. In contrast, the bourgeoisie’s tastes are tastes of luxury or freedom enabled not only by one’s possession of economic capital but also by that of cultural capital” (Rocamora 242). Bourdieu’s notion applies to both “une Chinoise” as well as the reader, who both need money (economic capital) and awareness (cultural capital) in order to participate in luxury and extravagance depicted for consumption in La Gazette du Bon Ton. According to Bourdieu, one’s taste is a marker of class, “taste classifies and it classifies the classifier” (Rocamora 242). The “taste” of “une Chinoise” exemplifies that she has cultural capital because she knows about France, as well as Asia, and she also has economic capital because she can afford to wear a couture gown designed by Georges Douillet who was known to design gowns exclusively for ultra rich women. Similarly, the reader of La Gazette du Bon Ton also has economic and cultural capital because the reader is aware of the luxuries in life and this “journal of good taste” both steers and influences them.

Works Cited

Chakraborty, Shruti. “Is Rajinikanth’s Party Symbol the same as Apana Mudra for ‘Detoxification and Purification’?” The Indian Express, http://indianexpress.com/article/india/rajinikanth-politics-party-symbol-apana-mudra-detoxification-purification-5007863/. Accessed 30 March 2018.

“Cultural Appropriation”. 4th ed., Cambridge Dictionary, 2018.

Davis, Mary E. Classic Chic: Music, Fashion and Modernism. Oakland, CA: University of California Press, 2008

“Hair Today…A History of Wigs”. The Post Magazine, 1 March 2017, http://www.thepostmagazine.co.uk/brightonhistory/hair-today-history-wigs=

“Masonic Hand Signs Exposed.” Veritas Vincit: The Truth Shall Prevail, 18 Jan 2015, https://veritas-vincit-international.org/2015/01/18/hand-signals-of-freemasonryexplained/

“Orientalism”. Oxford Dictionary, 2nd ed., 2018.

Percoco, Cassidy. “Georges Douillet”. A Most Beguiling Accomplishment, 22 Oct. 2014, http://www.mimicofmodes.com/2014/10/georges-doeuillet-1865-1930.html. Accessed 30 March 2018.

Popovic, Mislav. “Kasa – Traditional Japanese Hats”. Traditions Customs, http://traditionscustoms.com/traditional-fashion/kasa-traditional-japanese-hats. Accessed 6 April 2018.

Rocamora, Agnes. “Pierre Bourdieu The Field of Fashion”. Thinking Through Fashion, edited by Agnes Rocamora and Anneke Smelik, I.B Tauris & Co. Ltd., 2016, pp. 233-250.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. London, Penguin, 2003.

Weill, Alain. La Mode Parisienne La Gazette du Bon Ton 1912-1925. Paris, Bibliothèque de L’image, 2000.

V&A. “Style Guide: Chinoiserie”. Victoria & Albert Museum, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/s/style-guide-chinoiserie/. Accessed 6 April 2018.

Young, James O. Cultural Appropriation and the Arts, John Wiley & Sons Incorporated, 2008. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral-proque.com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/lib/ryerson/detail.action?docID=351045.