“If you were going to compress into a time-capsule the very essence of January 1, 1950, for a future world to find, what would you put into it?…. A recording of “Some Enchanted Evening”…. A short evening dress…. A string of baroque cultured pearls…. A bale of cut-off hair…. Long white gloves…. A copy of the January 1900 issue of Vogue, and this one.” (“Vogue’s Eye View of Now” 1950).

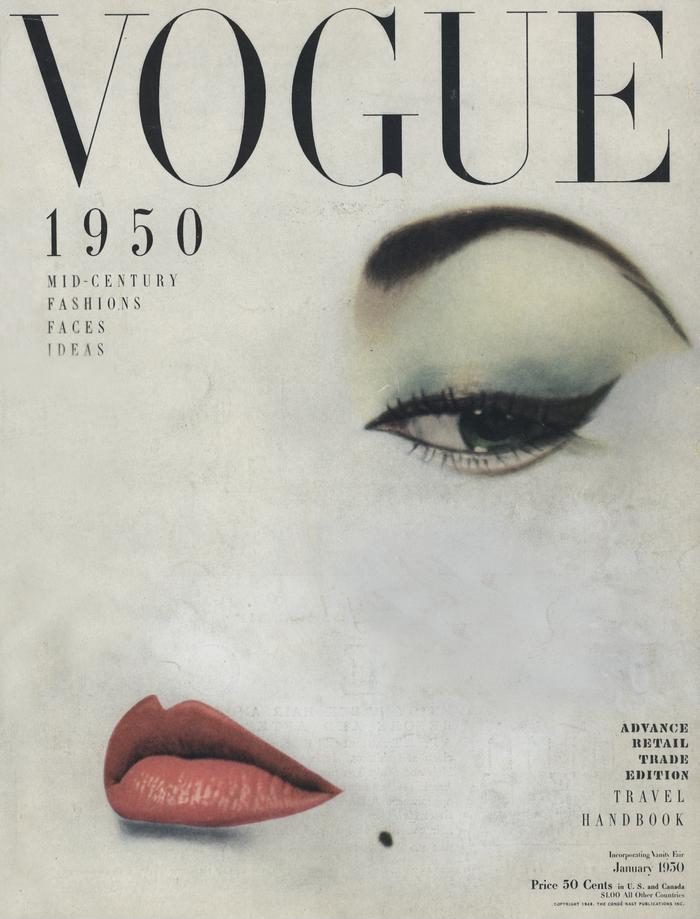

♦ It was the dawn of the 1950s—a time characterized by rock and roll, the Studebaker, widespread consumerism, and, in the realm of high fashion and beauty, new hyper-feminine, waist-whittling fashions for women and the doe-eyed model who wore them best, Jean Patchett (1927-2009). With a single sweeping brow, a boldly lined eye, cherry lips, and a penciled beauty mark, Patchett appeared on the 1950 January cover of Vogue (pictured left), subsequently becoming the face of a decade. Like the growing economy and population at that time, the cover hit newsstands with a ‘boom’ so powerful that a variation of the Patchett’s doe-eyed look reverberated into the sixties; kohl liner was applied to the lids, not with a carefully drawn flick, but liberally for a smouldering effect (think Edie Sedgwick’s bold eye makeup) to match the daring new sixties style, complete with A-line tailoring and architecturally inspired garments (Astley 349).

Big and bold eyes were, in fact, de rigueur for the 1950s face as an article from the same Vogue issue titled “The Mid-Century Beauty” insists (article pictured right). A makeup look as “excitingly new” as the use of lipstick in the twenties, the doe-eye, adopted from Paris-based fashion designer Robert Piguet, could be achieved with the freehanded sweep of a soft eyebrow pencil or kohl from the inner-corner of the eye to the outer-corner, then extended up toward the brow and tapered to a point (Vogue 113). Paired with a sleek pixie cut, two-toned eyeshadow, a matted face, and a bow-shaped mouth (Vogue 113), this attention-grabbing appearance was a contrast to the more “natural” face of makeup worn by women during the previous war-torn decade which consisted of subdued eyes and a pink or red lip.

Jean Patchett interview with Edward R. Murrow on Person to Person for CBS Television, January 8th 1955. Jean demonstrates how to apply makeup for a doe-eyed effect and shows off pyjamas featuring her face from the January 1950 cover of Vogue (above).

In this way, the doe-eye signified a distinct transition from a past makeup practice and appearance to a new mode of makeup specific to the fifties. The January 1950 Vogue cover of Patchett, by extension, is a production, or a simulacrum in Baudrillard’s terms, of a new beauty ideal set in motion by the magazine publication and its then team. In this vein, Patchett’s singular doe-eye pictured on this cover is synonymous with the Vogue’s eye view—one that was focused on adapting the 1950s face to suit the break out of a Coca-Cola drinking, jukebox playing, Elvis Presley swaying youth culture that set itself apart from the “old hauteur” (Rule 2002). As a Parisian-inspired look, the doe-eye strongly signified this transition, and was a hat tip to the decade’s golden age of haute couture for which Patchett became the face. Even renowned fashion photographer Irving Penn, whom adored photographing Patchett, identified the model as “a young American goddess in Paris couture” following her death from emphysema at the age of seventy-five in February 2002 (qtd. in Horyn).

As a woman who, in photographs, exuded rebellion and a slight attitude that connected her to Europe’s ‘knowing girls,’ Patchett herself seemingly deviated from the traditional “white glove” society of 1950s America (Rule 2002). That said, Patchett’s day-to-day personality and reputation in the modeling world could not have been more opposite. Counterparts like fashion model Dolores Hawkins repeatedly praised Patchett for her well-mannered behaviour and politeness: “She treated everyone graciously; models, the girls who fitted our outfits, and photographers. Jean was always professional and wonderful with everybody” (qtd. in “An American Goddess of Paris Couture”). Despite her kind charm, best exemplified by her go-to introduction to editors (“I’m Jean Patchett. You don’t darn it. You patch it.”), Patchett admitted to having acted as an ‘ice queen’ during her photoshoots, developing the “Glacier Look”—the Blue Steel of its day—which American model Dovima (Dovima with the Elephants) also adopted in her work (Rule 2002; Lebland and Vaillat). In this way, while the Glacier Look connotes a sense of rebellion, it is merely an act, and thus none other than myth (Barthes).

The January 1950 Vogue cover is a retouched copy of American fashion photographer Erwin Blumenfeld’s black and white photograph of Patchett (pictured left) (Rule 2002), in which all of the model’s facial features are visible—her eyes appearing fixed on the camera with the same gaze as in the cover photo. Patchett’s doe-eyed makeup, which she applied herself as most mid-century models did, was Blumenfeld’s idea (Rule 2002). Under the advisement of art chief Alexandra Liberman, the up-close portrait of Patchett was stripped down and cropped to the cover that readers are familiar with today (Rule 2002). This process does not render the photo devoid of meaning; rather, by reducing the image to Patchett’s eye, brow, and lips, the cover becomes a sign of a change, and, by extension, a signification of the decade’s new beauty standards. Vogue was a beacon for new trends and attitudes in fashion, as it continues to be today.

On a deeper level, this method of cropping also speaks to the way in which women’s garments, although more widely available, were becoming increasingly restrictive—the prevailing silhouettes being the New Look hourglass and the glove-fitted slim line were reactionary in their remolding of the female body, and structured bras, corselets, hip pads, and stiffened crinolines suppressed women’s waists and emphasized women’s breasts and hips, thus subverting the liberation of women’s bodies from the 1910s through to the 1930s (Borrelli-Persson 2017; Koda and Yohannan 13). Also ‘cropped,’ a shorter hairstyle surely made it easier and less time consuming for women to coif in the morning, while also drawing attention to their doe-eyes—doe-eyes recalling a female deer, a symbol, not so much of intelligence, but of innocence and nurturing, and, above all, evocative of a gentle femininity. Could the doe-eye trend have been an inconspicuous message for women to retreat back to the domestic-sphere of the home and get busy making babies after a period fraught with war? Absolutely. To make an even stronger case, in Disney’s Bambi, released in 1942, Bambi’s mother represents the epitome of a nurturing mother figure, sacrificing her life, as Dr. Alison Matthews-David from Ryerson University points out, for the safety of her fawn. With the doe-eye, then, women could be stylish, mothers, and domestic-doyennes at once. As such, the doe-eye was more than a mere beauty trend; complimenting women’s hyper-feminine silhouettes of the day, it gave women a model to aspire to, both literally and figuratively.

Along with Irving Penn’s black and white photograph of Patchett for the April 1950 Vogue cover (pictured right), the January cover has become iconic. The photographs that Penn took of Patchett were simulacra of sorts, as well; they were a series of collaborations between the artist and model of movie-like scenarios—a bedroom phone call from a departed lover, or a boyfriend late for a theatre date—captured in stills (Rule 2002). As Charles Gandee writes in an article for the January 2000 issue of Vogue, Penn allowed Patchett to “use [her] head,” providing her with a story for each shoot that she could enact (Vogue 2000 pp. 176). These photographs, the stories they are meant to tell, and the settings depicted within them, in this way, are simulacra of actual places and times. Unlike the departed lovers and no-show boyfriends, the men who courted Patchett in real life were often the wealthy elite members of the Stork Club, one of the most prestigious clubs in the world located in Manhattan, New York City; however, she rejected them all for Louis Auer, a banker she met in 1948 and later married and had a child with (Rule 2002).

It goes without saying that Patchett, whose career spanned three decades (from 1948-63) (“An American Goddess of Paris Couture”), has become a fashion icon herself. With over forty magazine covers to her name, and innumerable editorials and advertisements in high-fashion publications like Harper’s Bazaar, Elle, Glamour and, of course, Vogue (Milwaukee Journal 2002), Patchett unequivocally holds a significant place in the fashion world. The January 1950 Vogue cover is only one of the many striking covers she appears in, yet this cover in particular recently inspired that of another: Harper’s Bazaar emulated the iconic cover for their December 2010 issue featuring pop-singer Katy Perry (pictured left). From a semiological perspective, the photograph of Perry is a sign that not only signifies the singer herself, but, in this case, the woman she is modeled after, which is a connection requiring a certain cultural and social capital to recognize (Barthes; Bourdieu). With her arched eyebrow, bold eyes, and rhinestone studded lips, Perry is a modern representation of Patchett, while the cover itself symbolizes a contemporary take on the 1950s face. The image is captured by a lens focused on the time of high glamour—hello, rhinestone studded lips!—we live in, simultaneously pointing to the ceaseless evolution of beauty and style from decade to decade, and the power of a single image even half a century later.

♦

Special thanks to the Royal Ontario Museum Library for allowing access to their outstanding fashion archive.

Discussion Questions ♦ When we, as viewers, read into an editorial or magazine cover—or any image, for that matter—do we take away from its artistry, or simply add to it? How can semiological readings deepen our understanding of fashion/art images?

Works Cited

“An American Goddess of Paris Couture: Jean Patchett.” Jean Patchett, jeanpatchett.com/.

Astley, Amy. “Health & Beauty: Making Eyes.” Vogue, vol. 184, no. 11, Nov 01, 1994, pp. 347-347, 348, 349, ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest- com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/879302160?accountid=13631.

Borrelli-Persson, Laird. “The History of ’50s Fashion in Vogue, Narrated by Sarah Jessica Parker.” Vogue, 19 June 2017, www.vogue.com/article/vogue125-video-fashion-history-sarah-jessica-parker.

Gandee, Charles. “Fashion: Faces to Remember: 1940/1950.” Vogue, vol. 190, no. 1, Jan 01, 2000, pp. 176, ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest- com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/904353512?accountid=13631.

Horyn, Cathy. “Jean Patchett, 75, a Model Who Helped Define the 50’s.” The New York Times, 4 Feb. 2002, www.nytimes.com/2002/02/04/nyregion/jean-patchett-75-a-model-who-helped-define-the-50-s.html.

“Jean Patchett.” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, Feb 08, 2002, pp. 4, ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest- com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/261561891?accountid=13631.

Koda, Harold, and Kohle Yohannan. The Model as Muse: Embodying Fashion. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.

Lebland, Romuald, and Vaillat, Jessica. “Jean Patchett.” The Red List, theredlist.com/wiki-2-24-525-528-721-view-1950s-4-profile-jean-patchett.html.

Rocamora, Agnes, and Anneke Smelik, editors. “Jean Baudrillard: Post-modern Fashion as the End of Meaning.” Thinking through Fashion: a Guide to Key Theorists, by Llewellyn Negrin, I.B. Tauris, 2016, pp. 215–232.

Rocamora, Agnes, and Anneke Smelik, editors. “Roland Barthes: Semiology and the Rhetorical Codes of Fashion.” Thinking through Fashion: a Guide to Key Theorists, by Llewellyn Negrin, I.B. Tauris, 2016, pp. 132–148.

Rocamora, Agnes, and Anneke Smelik, editors. “Pierre Bourdieu: The Field of Fashion.” Thinking through Fashion: a Guide to Key Theorists, by Llewellyn Negrin, I.B. Tauris, 2016, pp. 233–250.

Rule, Vera. “Obituary: Jean Patchett.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 8 Feb. 2002, www.theguardian.com/news/2002/feb/08/guardianobituaries.

“Vogue’s Eye View: Vogue’s Eye View of Now…Right Now, of January 1, 1950.” Vogue, vol. 115, no. 1, 1950, pp. 85, ProQuest, http://ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/login?url=https://search-proquest- com.ezproxy.lib.ryerson.ca/docview/904323731?accountid=13631.

You write in such a beautiful way! I really enjoyed reading both of your posts. I think that you did a great job relating historical points, such as the war, to your analysis. It is very interesting to see how fashion is cyclical and how publications such as this one from Harper’s Bazaar may try to bring the past back by emulating it. I also think that the way you explored layers of meaning to understand her eyes was very well done, bringing to attention several points that I might not have thought of when just looking at the photo.

A shoutout to this phrase “With the doe-eye, then, women could be stylish, mothers, and domestic-doyennes at once”, that is part of an important movement that we are living to this day.

Hi Adriana! You did a fantastic job exploring the various layers to this Vogue cover. I was fascinated to learn what was in vogue in the 1950s in regards to make-up aesthetics such as perfectly sculpted arching brows, boldly lined winged black eyeliner and rouge lips.

It is also interesting that this look became the face of that decade and its popularity and overall aesthetic continues to resonate today. What I love about this Vogue cover is that it is artistically timeless. The application of make-up and the close-up photograph of Jean Patchett by Erwin Blumenfeld for Vogue in 1950, is beautifully timeless. I found it interesting to note that the thinly lined waterline, the smoky outer corner of the eye, lightness in the middle of the lid and depth in the corner of the eye are all techniques that are still relevant in North American beauty today. I loved your inclusion of multimedia such as the video of Jean Patchett demonstrating how to apply make-up. It gave us a real glimpse into her approach. Your comparison of the Vogue cover of Patchett and Baudrillard’s simulacrum was very appropriate and I enjoyed reading your comprehensive interpretations.

I agree you have a very nice writing style and I enjoyed reading and learning from your post! I was unfamiliar with the term doe-eye and mid century make-up in general, and yet I am a good case study of just how powerful signs are, as even though if someone asked me to articulate the make-up look of that time I would think that I could not, when I look at the image cover I am able to recall the time in fashion, a sign, that the signifiers are in good working order! In answer to your discussion question, I think absolutely that the semiological readings of fashion imagery is key to doing better creative work and that Baudrillard’s Simulacra clearly shows us the problem we have today – as most viewing the 2010 cover for example would never know that it is a recreation of an earlier version, or realize for example that a new music track is actually heavily sampled from a past musical piece etc. If we can see the imagery within its cultural progression and its influences, and recognize the messages and associations to the society in which it is situated, we can glean more from it and in turn point ourselves to more original approaches to working with fashion.