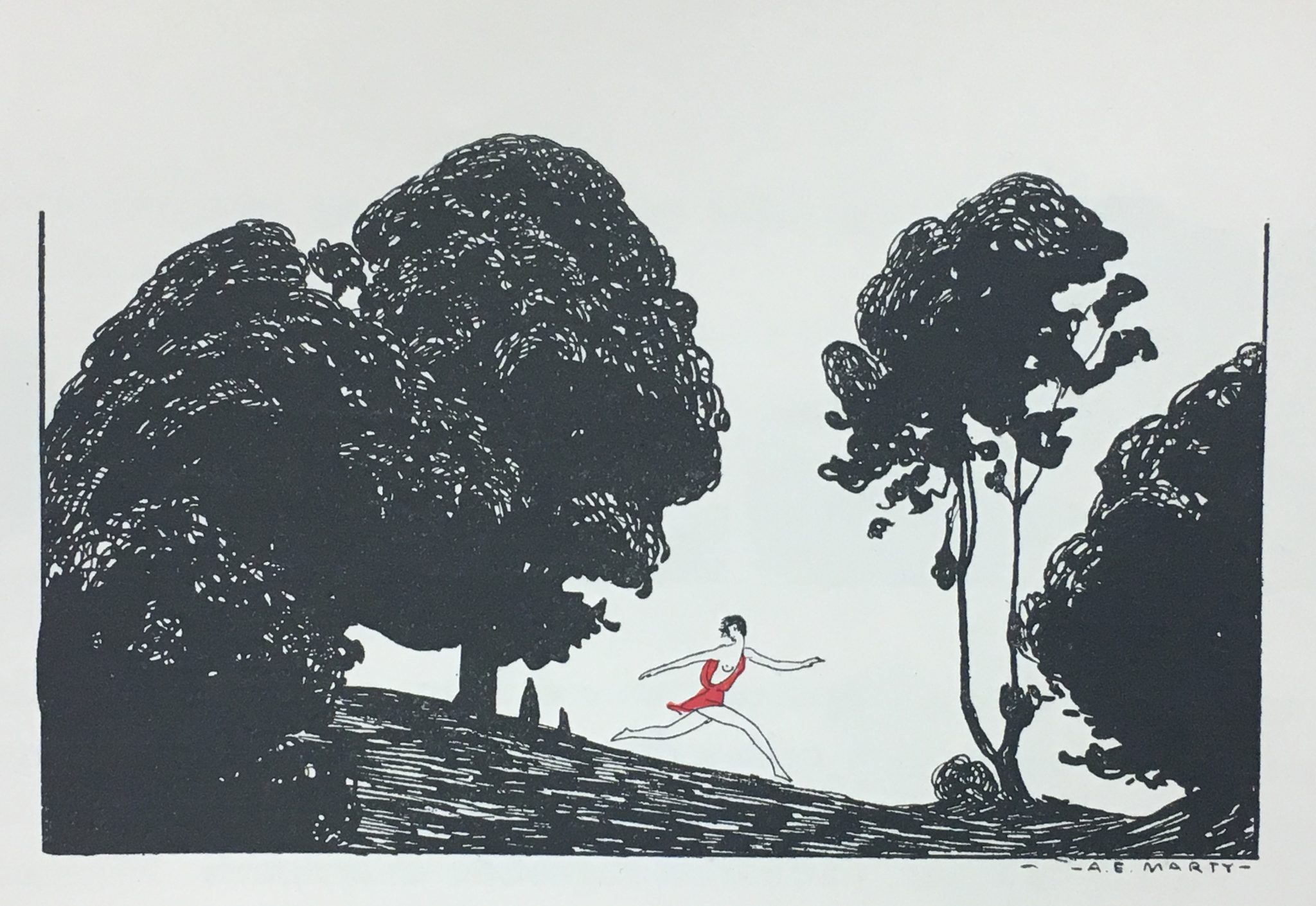

A petite figure in a short red chiton is gracefully bounding through a lush forest meadow. Her limbs are long and lanky, her hair cropped short and loose, her skirt flowing up to the crease of her leg and her breast is exposed (Fig.1). It is Atalanta, the classical Greek beauty known for being the fastest runner in the Ancient world. Her story goes that her father wanted her to get married, but she wanted to stay an independent adventurer.

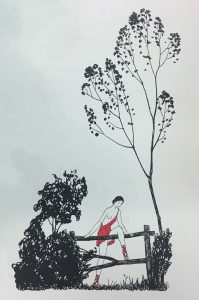

She was the fastest runner in the world and the one to draw first blood in the great Calydonian Boar hunt (Fig. 2), she didn’t need some man holding her back! Atalanta and her father made a deal that if a man could beat her in a race, she would marry him. Knowing she was an incredible athlete, her father devised a plan with Hippomenes to drop golden apples to distract her during the race (Fig. 3)(Gori, 2012, 206), playing into the concept that woman are the mental equivalent of magpies (but that’s a whole other story).

When observing illustrations of Atlanta, I really have to question how the fastest runner in the world felt about having her one boob out flopping in the wind. Over and over she is depicted in the official Heraia chiton worn by female athletes (Serwint, 1993, 404).

Like Atalanta, the Amazons were also icons of female athleticism in the ancient world. Amazons were a matriarchal society of warriors and their solution for the pesky lack of sports bras? The legends say that they seared off their right breast. Better for using a bow and arrow or throwing a spear. These terrifying warrior women represented the fears and anxieties surrounding empowered female athletes (Johnson, 2017) going back thousands of years.

Their solution was pretty extreme, but the real kicker: woman have wanted to be comfortable while active since the ancient world, but the sports bra wasn’t invented until 1977!

La Gazette du Bon Ton provides an insight into the attitudes that kept woman from wearing comfortable and functional undergarments when it came to any athletic endeavours.

The 1924 article used classical narratives to discuss the hottest trend of the 1920s. Lanky limbs, short hair, and a short flowing dress; sound familiar? Author George Barbier was drawing a parallel between Atalanta and the Flapper. Both young, independent women, and just a little too wild for his taste. The beautiful illustrations by André Édouard Marty show Atalante’s athleticism and talent for archery. She is alone (save for a trusty-pup companion) out in nature running, climbing, shooting, and bathing (Fig. 5 & 6). Atalante is shown in idealized form while the article seems to be advising against the whole idea. Barbier acts as the voice of Atalante’s father, advising the readers on the perils of being an athletic young woman.

“Pour ma part, je les considère avec étonnement quand je les vois se livrer impétueusement a des jeux forcenés. Le corps féminin est trop fragile pour pouvoir, sans disgrace et sans peril, rivaliser sur le stade avec celui des athletes. Le football et la course a pied ne conviennent point aux dames, elles s-y épuisent vite et leurs nerfs sensibles les jettent parfois en des crises de nerfs ou en des pavoisons. — En: Personally, I consider them with astonishment when I see them impetuously engage in frenzied games. The female body is too fragile to be able, without disgrace and without danger, to compete on stage with those of the athletes. Football and running do not suit ladies, they are exhausted quickly and their sensitive nerves sometimes throw them in fits of nerves or vanity.” (Barbier, 1924)

Oh my! Although he is impressed by the ‘frenzied’ energy of active girls, he thinks this is not suited to a proper woman. He believes the “sweet but heavy chains of husband and child” far outweigh the appeal of competition. He also advises that men aren’t attracted to woman who participate too much in sport. Barbier wrote this article at the age of 42, and while “journalists and popular writers in the 1920s used readily recognizable stereotypes to portray the characteristics of both generations within popular literature. The younger generation was portrayed through representative middle-class, energetic figures who were born in the twentieth century, participated in the European War, and eagerly consumed the latest technology.” (Hirshbein, 2001, 114) The article referenced classical narrative as a way to critique the values of the Flapper without needing to critique the fashion itself.

He used another classical narrative of Phryne in front of the Aeropage to reinforce his moral stance on modesty. Phryne only showed the judges one beautiful breast, and they acquitted her of all charges, his article claims. Women require that air of mystery to be attractive, therefore participating in competitive sport and without proper ‘aesthetic girdles to constrain and reshape uncertain breast’ a woman is falling victim to excessive vanity. The Gazette du Bon Temps advises proper ladies to do some non-competitive activities, but participating in aggressive sport is absolutely immoral. It also is implied that adolescent females can participate in some sport, but once a husband comes along they must prioritize being a modest and dutiful wife. (Barbier, 1924)

Interestingly, the Olympics were held in France twice the same year this article was published. Chamonix hosted the winter games of 1924, and Paris hosted the summer games. Women could only participate in limited low-impact sports such as golf and tennis. In 1928, female participation increased to 10% when woman were allowed to participate in athletics, gymnastics, tennis, sailing, croquet, equestrian sports and golf (Olympic.org). These pioneering woman made do with the undergarments available and many of them seemed to reflect the waif-like flapper body type. The realities of the Olympics seem to echo the notion that sport is alright for adolescent female bodies only (Fig 8). I also assume not having access to appropriate undergarments makes it extremely uncomfortable for bustier woman, discouraging their participation in the first place.

The times were changing, and the influence of the independent, decadent, energetic and cynical American flapper had spread across the world (Cheadle, 2018). The Gazette du Bon Ton was using this article to reinforce the ideal French womanly woman, even when the silhouettes favoured a sporty body. The ideal body of the 1920s reflected a fashion problem: woman’s bodies had to look sporty, but they couldn’t be sporty.

Colette critiqued this trend in her satirical writing by advising woman to treat ‘your breast as a fashion accessory’ (Freadman, 2018, 337). Obviously, this is quite the challenge as boobs are attached to your body, but it didn’t stop woman from trying. Ladies in the 1920s aimed for the slim, undeveloped form and the bandeau bras and girdles of the time were designed to flatten out the breast to fit the tubular form (Feilds, 2007, 72). These solutions were not overly supportive, and certainly not encouraging for woman who wanted to engage in sport.

Although the 1920s brought about the end of corsets, the suffrage of American woman, and the fashionable athletic body ideal, the strong opposition to woman’s participation in sport did not encourage any innovation in the development of comfortable undergarments specific to sport. France was especially hesitant about accepting the modern woman: “The model of the flapper scared society. Female sport brought on suspicions of inverted sexuality and androgyny.” (Terret, 2010, 1160). For years woman had to make due with the undergarments available that were still somewhat restrictive or only developed specifically for acceptable feminine activities.

What needed to happen for woman to get the proper sporty support? Second-wave feminism! The 1960s and 70s were a transitional period. While the myth of bra burning got its roots, some woman just wanted to go jogging without nipple chafing. The early sixties and seventies had woman pushing for Equal Rights and a ’68 protest where demonstrators threw restrictive clothing items in a garbage can turned into the ‘media myth’ of bra burnings.

Though the concept of bra-burning was symbolic, the act of being comfortable above meeting social expectation became a revolutionary act. Even in the time of ‘going braless’ the general agreement was that bras are unequivocally necessary for comfort, not just to create a feminine form (Spencer, B. 2007, 238). Through the hard work of the equal rights movement, a law passed that had an impact on the tale of sports bras: Title IX in the United States legally guaranteed equal participation and benefits from education program receiving Federal financial assistance. Meaning female participation in school sports grew exponentially. (Ladd, 2014, 1681)

In the 70s ‘yogging’ was the hot new trend. Lisa Lindahl and Polly Smith were all about it but were tired of experiencing the discomfort that comes with bounding bosoms. Like many other women at the time, these ladies were problem-solving because the market wasn’t meeting female athletes’ concerns. (Bastone, 2017) If you would like to learn more about their story you can watch this great video: https://vimeo.com/174135593

In 1977, they had a revelation: the Jockbra. They had taken two jockstraps and transformed them into a jockstrap for breasts (Fig. 10). “The sports bra revolutionized support for the defining anatomic feature of the class Mammalia, and, paradoxically gave freedom for women athletes of all shapes and sizes to participate in sports unforeseen just a few years earlier.” (Ladd, A. 2014, 1681) The perfect combination of material technology and increased female participation in sport finally allowed the development of sports bras. Sports bras have continued to develop to meet the needs of more and more woman who are participating in as many competitive and non-competitive sports as they please.

Thanks to the sports bra female athletes can exist beyond adolescence and in a multitude of sizes. As new technology is developed, sports bras and athletic gear, in general, will get more and more accommodating to ALL athletes. I’m sure when Barbier advised ladies play tennis as a non-competitive option for exercise, he could never have imagined bad-ass babes like Serena Williams (Fig. 11) pushing sport and fashion to work for women and not the other way around.

On a final note, I like to think Atalanta finally got her sports bra. In this 1974 animation, her story is reimagined with a feminist twist and more comfortable looking sportswear indicative the forth-coming sports bra. https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=23&v=q-77_cVnmUQ

You go girl!

Works Cited:

Angelone, D. J. & Swirsky, J. M. (2014). Femi-Nazis and Bra Burning Crazies: A Qualitative Evaluation of Contemporary Beliefs about Feminism. Current Psychology, 33(3), 229-245.

Bastone, K. (2017). A Brief History of the Sports Bra. Runner’s World. Retrieved from https://www.runnersworld.com/sports-bras/a-brief-history-of-the-sports-bra

Barbier, G. (1924). Atalante. Gazette du BonTon: Art, Modes & Chronique, 6(6), 225-228. Retried from the ROM Library Archives.

Cheadle, T. (2018). The Invention of the Flapper: More than a symbol of decadence, the flapper should be seen as a quest by women for agency, independence and escape from domesticity. History Today, 68(2). Retrieved from https://www.historytoday.com/reviews/invention-flapper

Fields, J.(2007). Corsets and Girdles. In An Intimate Affair: Women, Lingerie, and Sexuality. University of California Press.

Freadman, A. (2018). Breasts are Back! Colette ‘ s Critique of Flapper Fashion. French Studies: A Quarterly Review, 60(3), 335-346.

Terret, T. (2010). From Alice Milliat to Marie-Therese Eyquem: Revisiting women’s sport in France (1920s-1960s). International Journal of the History of Sport, 27(7), 1154-1172.

Gori, G. (2012). Prologue : Atalanta as Symbol of European Sportswomen. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 29(2), 206-211.

Hirshbein, L. D. (2001). The Flapper and the Fogy: Representations of Gender and Age in the 1920s. Journal of Family History, 26(1), 112-137.

Johnson M. (2017). The truth about the Amazons – the real Wonder Women. The Conversation. Retrieved from http://theconversation.com/the-truth-about-the-amazons-the-real-wonder-women-78248

Ladd, A. L. (2014). Gendered Innovations in Orthopaedic Science Game in Play Gendered Innovations in Orthopaedic Science. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 472(6), 1681-1684.

Serwint, N. (1993). The Female Athletic Costume at the Heraia and Prenuptial Initiation Rites. American Journal of Archaeology, 97(3), 403-422.

Spencer, B. (2007). Bras, Breasts and Living in the Seventies: Historiography in the Age of Fibs. Australian Feminist Studies, 22(53), 231-245.

Key Dates in the History of Woman in the Oylmpic Movement. (2018). Olympic.org. Retrieved from https://www.olympic.org/women-in-sport/background/key-dates

I’ve been doing research on what women have historically worn for sports participation as well, and I was also struck by how long it took for the idea of actual performance-enhancing garments to enter the conversation. It seems so ridiculous now that you can see athletic wear on the streets in almost equal measure with regular street clothing, but we really were encouraging women to try and compete-athletically-in dresses! For so long! I had no idea that the proto-sports bra was made of jock straps, though. Talk about innovation.

I loved learning the story of Atalanta – she actually looks so happy and content in Marty’s illustrations, despite Barbier’s killjoy captions. How fascinating that legend of the Amazons says that they seared off their right breast (ouch!) to make their bodies more efficient for shooting, when all they really needed was a sports bra.

There are some interesting comparisons in your post and mine on how fashion and sports came together in the 1920s, and what that meant for the female body. I found it stressful just reading about the pressures of the waif silhouette, but on the other hand, it was probably super freeing to be rid of all those cumbersome undergarments.

I will hug and thank my sports bras before I go to bed tonight.

Just wanted to add that I showed my daughter Sasha the post and she who has grown up in an era where athletic clothing is available was entranced and amused by the jockbra (although I had to explain what a jockstrap was)… thanks for such a great post and I agree that both of your posts intersect beautifully!

Presley, I really enjoyed reading your blogpost. I love how you approach your topic, using Atalanta as a starting point. I was pretty shocked to learn that sports bras weren’t invented before 1977, especially considering how much impact sports had on female fashion in the early nineteenth century. The belief that women shouldn’t participate in sports is really interesting, considering that women had been dancing ballet (and other forms of dance) for centuries. I’m not sure how ballet dancers would have been able to perform without any type of breast support…or would their corsets have been enough? Atalanta also seems to be wearing ballet shoes in certain images, which is interesting that the author would have positioned her in that field. Indeed, I don’t know if it was still the case in the twentieth century, but prostitution was often connected to baller dancers. I also find it quite interesting how in the plate, only Atalanta’s dress, shoes and arc are red. Since the colour red is so often associated with female sinful activities and overt sexuality, I find that the use of the colour automatically links the character with immoral manners. Overall, I find it very disturbing how far female repression went and I think your blogpost highlighted a very important part of fashion history that I wasn’t aware of.

That is such a good insight about the colour red!! Upon reflection, I am sure that was the intent of the illustrator: to position Atlanta as sinful. I also didn’t think about ballet as my research lead me down the Olympics rabbit hole. I think that the ballet dancer’s body reflects the ‘acceptable’ body for sports at the time and really does demonstrate the intersect of athletics, sinfulness, sexuality, and idealized bodies.