Who wears hats anymore?

Bygone are the days of women and men wearing extravagant hats; or so it may seem. Hats inspired by the victory of La Belle Poule and popularized by Marie Antoinette in the 1700s (shown right) would be considered outrageous walking down a street in 2018. Even simple hats such as the pillbox popularized by Jackie Kennedy in the 1960s (show below right) appear to be out of period movie. Does that mean then that no one is wearing hats anymore?

What was once a common part of everyone’s outfit (both male and female) has now been relegated to something most commonly worn only to baseball games or to survive harsh winters. The exception would be in Great Britain, where it appears that millinery is surviving but only really for the upper classes. Born at a time when millinery was still the norm, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II (born 1926) is keeping the accessory alive through her and her family’s fashion choices. Notable British milliner, Philip Treacy credits the Queen for “[keeping] hats alive in the imagination of people all over the world” (qtd. in Greenstreet “Q&A: Philip Treacy). Often those in the Royal family and those going to events hosted by the Royal family are expected to wear a hat. Often it is even explicit within the dress code whether a hat should be worn (as seen on the Royal Ascot website). It is worth noting that hats are only required for the “Royal, Queen Anne, and Village Enclosures” not the “Windsor Enclosure,” which one can assume is where tickets are the cheapest and not filled with the upper classes (Royal Ascot website). Consequently, we often associate hats with Her Majesty’s garden parties at Buckingham Palace, royal weddings, and the Royal Ascot—all places for the upper classes.

Does this mean then that no one wears hats unless they are at royal events, at a sports game, or in the cold?

The answer to that is not an easy one since one rarely sees someone wearing a “fashionable” hat (opposed to a practical hat such as a winter toque or a police hat) today yet the millinery industry is still alive. One of the people keeping millinery alive in the late twentieth and into the twenty-first century was undoubtedly Kathleen Kubas (born 1938)—affectionately known as Toronto’s “Hat Lady” until her death in 2008 (“Kubas Obituary” Toronto Star). Fortunately, her extensive millinery collection of over 300 hats lives on within Ryerson’s Fashion Research Collection. Her collection featured a wide variety of hats purchased throughout her lifetime of living in Toronto including some even from the early 2000s. These hats were designed by a variety of milliners including some Canadian and some from top “designer” milliners such as Stephen Jones and Philip Treacy (Mida “The Kathleen Kubas Collection”).

In closely investigating several of the hats using Mida and Kim’s methodology put forward in The Dress Detective, it was clear that these were in fact worn objects and not just a collection. Although initially, they may all seem to be in pristine condition; the fronts of the sweat bands (an inner band running the circumference of the hat) in most of the hats have stains or the remains of makeup from her forehead. This may be an obvious sign of wear, but with such a large collection it indicates that Kubas was regularly wearing all of her hats. This wear can be seen in the images below.

Why did people like Kathleen Kubas wore high-end millinery (and other continue) when hats have fallen out of the norm, especially in a place like Toronto?

The decline of the hat came alongside a slow change in social order following World War II that saw more women entering the workplace, a place not demanding a hat (Debo 27). Eventually it was just upper class left not working and still wearing hats, such as the Royal Family. Therefore, mainly high end milliners remained and could thrive, making the hat a luxury item, like those created by Stephen Jones or Philip Treacy. If the hat today then is a luxury item worn by women, then one might assume that Thorstein Veblen’s theories on conspicuous consumption would apply. Veblen theorized that fashion is used as a tool to show off one’s wealth or one’s place in society. He wrote “it has in the course of economic development become the office of the woman to consume vicariously for the head of the household; and her apparel is contrived with this object in view” (Veblen 344). If hats have high price tags attached, then all upper class women today should be wearing hats to show off their wealth. As previously examined the Royal Family and women attending the Royal Ascot are prime examples of this; however it does seem to fit all women with wealth. For example, the millinery department that once existed within Holt Renfrew (BAK “Holt Renfrew & Company LTD.”), a Canadian high-end department store where Kubas purchased many of her hats, is no longer there, suggesting that luxury female consumers in Toronto are not purchasing millinery to the same extent that they once were. Veblen’s theory appears to be a semi-legitimate argument for wearing hats; however it does not seem to fully capture why people still wear hats in the twenty-first century.

Although Kubas was clearly able to afford designer hats, such as those produced by Jones or Treacy, her occupation as a grade 1 school teacher (as indicated in her obituary) does not necessarily give her the same economic position that Veblen was writing about. Following Riello’s methodology of material culture, he wrote that by studying the object we are not looking at the object itself nor theories, but we are looking at the different meanings that objects can take on (Riello 6). The hat itself can be studied as a work of art, but as earlier indicated, it gives us a larger picture of who Kathleen Kubas was. As a former model and actress, Ms. Kubas remained a creative individual expressing herself through the garments that she wore. Studying the hat with this methodology provides an alternative narrative that people other than the Royal family wore hats throughout the last half of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first century. Likewise, Bethan Bide wrote: “Worn over a long long period of time, these garments speak of lingering and changing experiences rather than representing the brevity of a passing fashion trend or a single occasion of wear” (Bide 453). Similar to Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Kubas would have begun wearing hats at a young age when they were still fairly popular among the middle and upper classes. They study of her hats prove the fact that women like Kubas continued to wear these objects even though they had fallen out of mainstream fashion. They were a part of a complex system that made up the individual wearer’s identity.

Who then, is wearing millinery still today, and why?

To answer this question, one truly has to look at the hats themselves. Looking at an example of a black straw, women’s “top hat” (FRC 2009.01.12) from Kathleen Kubas collection at the FRC designed by one of the top milliners of today, Philip Treacy, one can see it is a statement hat. This object is variation of a top hat since it breaks many of the traditional rules for this style. It is made out of straw not felt; it is made for a female head not a male head; it is asymmetrical in the shape and size of the brim as well as the crown of the hat; it has a slight tear drop shaped crown referencing a fedora style; and it features a large assemblage of feathers on one side. Treacy masterfully updated the tradition of a top hat in this contemporary hat.

Although filled with these unusual nuances that make the hat unique, it is truly the large bouquet of black feathers that attract the viewer’s eye to it. It is a collection of small plumage feathers with long stripped feathers giving the bouquet a sense of drama and extravagance. The stripped feathers twirl and extend in what seems to be a variety of directions, though upon close examination, it is clear that they are precisely placed within the bouquet (pictured below).

When one views this hat within the Kathleen Kubas collection, it does not feel out of place even though it may be slightly eccentric. All of her hats have this element of whimsy and theatricality, quite often through the use of feathers or flowers against shapes that are simple yet slightly unique. When viewed within the oeuvre of Philip Treacy, this hat does not stand out as being extravagantly eccentric. His hats truly often balance this line of simplicity and tradition with slightly nuanced variations (such as the shape of the brim or the colour) with crazy eccentricities and unique features. Although this hat was made over ten years ago, in his current AW17 collection of hats, similar hats can be found today such as hat OC368 (pictured below right).

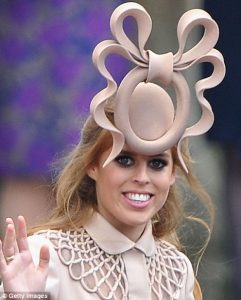

Kubas’ examples of Philip Treacy’s hats definitely fit within the “safe” or “ordinary” realm of his work. In fact, what Treacy is more known for is his completely over the top hats that truly act as pieces of art or sculpture. As a notable British millinery, Treacy has obviously designed hats for every member of the Royal Family, but noteworthy hats include the one worn by Camilla Parker Bowles at her wedding to HRH the Prince of Wales or the one worn by Princess Beatrice at the wedding of the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge (both pictured below).

Hats such as these are undeniably large statements. There are no practical benefits to wearing one of these hats. As for the case with the FRC’s Treacy top hat, an interior tag reminds wearers not to wear the hat in the rain because of the delicate nature of the feathers and shape of the straw. Instead, these hats are pure decoration and ornamentation. They are works of art for the head. They reflect a certain type of wearer—one who can afford this luxury item and is not afraid to stand out on the street. In her celebration of life ceremony, Kubas’ friends wrote “hats reflected her personality — extravagant, yet elegant and fashionable” (qtd. in Mida “The Kathleen Kubas Collection”). The hat in the twenty-first century is the highest accent of fashion. It tops off any fashionable look while still giving an indication of one’s taste and status. Geert Bruloot, a long time collector of Stephen Jones’ millinery, said “We collect fine art purely for ourselves…. Collecting Stephen Jones hats comes from an entirely different perspective, to show them, to share them with others” (qtd. in Debo 27). Similar sentiments could be expressed about Treacy and his millinery. Twenty-first century milliners have become fashion artists. Ellen Goldstein, accessories professor at the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) in New York, claims her millinery students work to “create a sculptural piece of art” (Zelevansky “Hats off to Modern Milliners”).

The twenty-first century hat has evolved. These hats are art, but art for the street. While hats may be continued to be exclusively attached to women from the Royal family or from upper classes, studying hats from Kathleen Kubas’ collection prove that other women still continued to wear hats. These women were not only fashionable but also purveyors of artistic fashion. That is why some women still chose to cover their head with a hat.

Works Cited

BAK. “Holt Renfrew & Company, Ltd.” The Department Store Museum. Apr 2011. http://www.thedepartmentstoremuseum.org/2010/06/holt-renfrew-co-ltd-toronto-ontario.html. Accessed 23 Feb 2018.

Bide, Bethan. “Signs of Wear: Encountering Memory in the Worn Materiality of a Museum Fashion Collection.” Fashion Theory: The Journal of Dress, Body, and Culture. 2017. 21:4, pp. 449-476.

Davies, Kevin. Philip Treacy. Phaidon, 2013.

Debo, Kaat. “Stephen Jones & the Accent of Fashion.” Stephen Jones & The Accent of Fashion. Lanoo Publishers, 2010.

Greenstreet, Rosanna. “Q&A: Philip Treacy.” The Guardian. 16 Aug 2014. https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/aug/16/philip-treacy-q-and-a-interview. Accessed 14 Feb 2018

Hats. March 1968. Vol. 92 No. 6. FRC 2014.99.168.

Holt Renfrew. “About Us: Our History.” http://www.holtrenfrew.com/store/holt/pages/about-us/our-history. Accessed 25 Feb 2018

“Kathleen Lonergan Kubas: Obituary.” Toronto Star. 29 Nov 2008. http://www.legacy.com/obituaries/thestar/obituary.aspx?pid=120715114. Accessed 08 Feb 2018.

Mida, Ingrid and Alexandra Kim. The Dress Detective: A Practical Guide to Object Based Analysis in Fashion. Bloomsbury Academic, 2015.

Mida, Ingrid. “The Kathleen Kubas Collection.” Ryerson Fashion Research Collection. 9 Sept 2013. https://ryerson-fashion-research-collection.com/2013/09/09/the-kathleen-kubas-collection/. Accessed 08 Feb 2018.

“Philip Treacy for Camilla Parker Bowles.” YouTube, uploaded by Victoria and Albert Museum, 13 Dec 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=diBIaFiSN48.

Philip Treacy London. https://philiptreacy.co.uk/en. Accessed 08 Feb 2018.

Riello, Giorgio. “The Object of Fashion: Methodological Approaches to the History of Fashion.” Journal of Aesthetics and Culture. Vol. 3. 2011, pp. 1-9.

Royal Ascot. “Style Guide.” https://www.ascot.co.uk/Royal-Ascot. Accessed 25 Feb 2018.

Veblen, Thorstein. “Dress as an Expression of the Pecuniary Culture.” Fashion Theory: A Reader edited by Malcolm Barnard, Routledge, 2007, pp. 339-346.

Zelevansky, Ellen. “Hats off to Modern Milliners.” T Magazine. 28 April 2015. https://tmagazine.blogs.nytimes.com/2015/04/28/female-milliners/. Accessed 14 Feb 2018.

I really enjoyed your perspective on what would motivate women to wear hats as well as the historical context that you are laying out here. It is definitely true that in today’s fashion sphere, wearing a hat is somehow quite a daring fashion choice and asks for a certain level of confidence as hats are most often considered as statement pieces. I liked you view on wearing hats as pure ornamentation as well as hats as works of art to which I would like to add a possible motivation for women to wear them which would be applicable into today’s reality. From my own experience I wear them either to make myself appear less approachable, or in a completely opposite way, to use them to connect more easily with others as they often serve as conversational pieces. In that sense, it is true that hats have this power of elevate someone’s look and make them seem more sophisticated. I would also suggest that hats have this power of bringing a certain feeling of mystery and in a way, are quite seductive!

So interesting that you use them to hide in a way. I guess it just depends on the style of hat, because some you definitely cannot hide in!

Very interesting Parker! I love how you challenged Veblen’s theories on conspicuous consumption, which at first may seem so relevant. I found the association with works of art really interesting, especially considering Kubas’ use of those hats. Indeed, your close examination of the collection reveals that she wore them often, which transform them from disconnected works of art to embodied accessories. When I associated the aspect of art with the embodied experience, it made me think about how beautiful hats are almost like performance art. It would also be interesting to try to find where Kubas wore her hats, because, as you mentioned, they aren’t very practical or easy to wear.

Thanks for you comment!

As far as I know, she literally wore hats every day. She was “Toronto’s Hat Lady” after all! I believe there are circa 300++ hats in the FRC from her collection, most bought at Holts. She originally was model and actress, but then taught grade one for most of her career. From what I read about her, she continued with teaching elementary reading after she retired (always wearing a hat!).

This was a great read, Parker. I know hats have a history in modesty. Women of upper classes and good reputation covered their hair, think Virgin Mary, and women who were slave women or concubines typically did not. Although I have not studied the history of this, I believe head-covering was the start of hats as fashion and it makes sense that women of stature would cover their head, although in quite a fashionable way now. I wonder how the modern hijab of today will evolve in decades to come? Will Muslims be wearing hats in the future? I love the video you shared. He truly is an artist. I wonder if he considers the wearer his canvass?

Fantastic and informative blog, Parker! I thought your writing flowed very smoothly. I was intrigued to learn about the origins of hat culture in Great Britain and I also enjoyed the way that you began your introduction with pictures, as well as questions, to immediately entice the reader to learn more.

Hats have so much personality and whimsy and I loved that you brought even more life to them through your research. Speaking of hats with personality, I have always been interested in the designs by Philip Treacy and I was happy to learn more about it through your research.

I also enjoyed how you used Veblen’s theories on conspicuous consumption as well as Riello’s methodology of material culture, and how Riello stated that “by studying the object we are not looking at the object itself nor theories, but we are looking at the different meanings that objects can take on” (Riello 6). I find it interesting to dissect the meanings that objects take on and how it gives us a larger perspective of who the wearer was. Great job.

Parker, I enjoyed reading your post on hats. I agree ‘fashion’ hats are worn by less of the population today, but they are still worn. It made me think of the larger, oversized hats which are trending with ‘fashion conscious’ consumers, as they adopt newer versions of the vintage Vivienne Westwood hat Pharrell wore to the 2014 Grammy’s. It also made me question why I had not yet worn the vintage 1970’s ivory felt fedora which I had blocked and cleaned this summer in preparation for the fall season nor the sage green fine wale corduroy Philip Treacy fedora purchased at Holt Renfrew on Bloor Street in 2005. Perhaps with my new student lifestyle, they did not fit in. As Women’s Trend Direction Forecaster at Hudson’s Bay, I can confirm that in 2006 through to 2008 hats continued to be a strong category and were forecast to continue for the next few years. They were mostly fedoras and the bohemian style wider brimmed hat; both offered in felt for the winter and straw for the summer. The dramatic statement hat with feathers was not considered ‘fashionable’ during this period. The move away from feathers may have something to do with PETA’s strong messaging and ads of the time which continue today. The wearing of hats in the 21st-century urban context is most likely two-fold. The first being merely functional in protecting one’s face from the damaging rays of the sun. The second could be a way of showing “one’s place in society,” as Veblen theorized, minus the economic component, or in modern day terms, belonging to their ‘tribe.’