Material objects have power over us. Referred to as “Thing Power,” Jane Bennett describes the power of the object as “the curious ability of inanimate things to animate … to produce effects dramatic and subtle” (351). We love our material objects, we treasure them, hoard them, buy multiples of them, we go into debt for them, we give them meaning and stature in our lives beyond the inanimate status they intrinsically hold (Stallybrass), and yet, they remain material. These material objects diminish, become unfashionable, and evolve into trash (Bennett). Although objects are inanimate and prone to ruin, they can bring stories, lives lived, and eras long gone back to life through material culture. An established method of research in Anthropology and Archeology, material culture reveals insights into history through the study of objects (Riello; Mida and Kim). In fashion studies, material culture analyzes the object with the aim to learn more about the lifestyle, time period, and values of that era (Riello). For instance, fashion history views the bikini as a sartorial object and places it along a timeline in the evolution of swimwear. Material culture recognizes the same object, then reveals how this particular piece of clothing is “a specific social practice during the second half of the twentieth century … [that refers] to a certain lifestyle, to the emancipation of women, to the opposition against right-wing bigotry in the 1950s and 1960s” (Riello 6). A material culture approach in fashion studies brings the past to life. In this blog post, I look forward to taking you on an autobiographical journey back to the 1980s, through the material culture analysis of one of my favourite sartorial objects from that time in my life, my 1987 Albert Nipon skirt suit.

The Power Suit Rises

In the United States, the National Organization of Women (NOW) was founded in 1966. This organization advocated for women’s rights and was devoted to fighting discrimination of women in the workplace. Made up of an older generation of women who had been fighting for women’s rights since the 1940s and 1950s, their focus was on making changes to the legal system and lobbying politicians. A younger generation of feminists, who followed NOW, began challenging NOW’s approach. These second-wave feminists exerted their demands by turning their backs on hegemonic ideals of femininity and, among other battles, fought for a woman’s right to wear pants to work (Hillman)! It was this younger generation that was behind the proliferation of the pantsuit for women in the 1970s. Third-wave feminists “championed women’s ‘choices’ in self-fashioning” arguing that “women’s liberation is strengthened when women can reclaim femininity as part of their individuality” (Hillman 176-177).

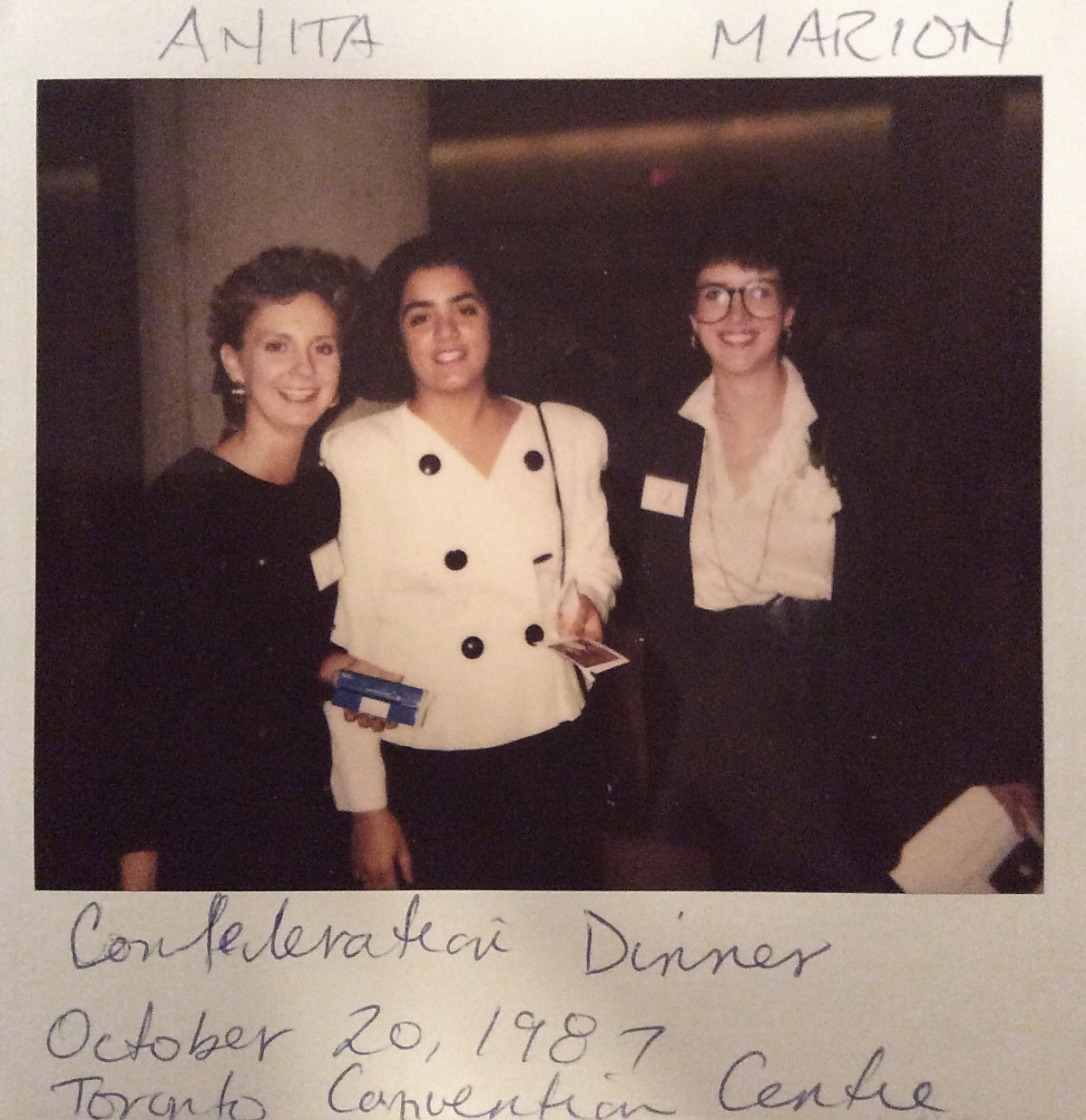

Source and Photo: Author’s personal collection.

In 1977, following the success of his book written for men, Dress for Success, John Molloy released The Women’s Dress for Success Book. This book along with third-wave feminism, was the start of a shift from polyester pantsuits to a look that brought the authoritative influence of the man’s suit to women’s career wear (Cunningham). Women aspiring for career success had to find a way to “escape the role of secretary, assistant, and employee … to find the armor that would … stop them from feeling out of place” (Frisa and Tonchi 123). Designers like Giorgio Armani began designing for a “woman who was not the man’s other half but his antagonist” (Frisa and Tonchi 125). By the 1980s “suited power-dressing [for women] became the norm” (WSGN 7). Women were asserting themselves in traditionally male-dominated workplaces and design elements such as shoulder pads, gave women’s dress a “masculine prowess” (Frisa and Tonchi). The padded shoulder silhouette lent “an imposing touch to the figure … perfectly cut to suit the female figure, [with] straight skirts … that leave the legs exposed” (Frisa and Tonchi 123). Frisa and Tonchi’s description of the power suit silhouette describes my 1987 Albert Nipon skirt suit exactly. This suit look – commanding, and feminine at the same time – came to be known as the “‘power look,’ accurately encapsulating the phenomenon of the career woman, her aspiration to get to the top, [and] the authoritative nature of her professional choices” (Frisa and Tonchi 125).

Thanks to second-wave feminists who had made significant strides toward the acceptance of women in politics and the workplace (Hillman), I began my professional career at the height of the power suit era, in 1986, working as an aide to a female politician and Cabinet Minister, the Hon. Elinor Caplan, Minister of Government Services and Chair of the Management Board of Cabinet in the Legislative Assembly of Ontario.

Power Suits Me

My 1987 Nipon skirt suit is one of my treasured 1980s purchases. I have carefully stored this suit for 30 years, protected from dust, mold, and decay. When I pulled it out of storage for this research, the Lipton’s label on the jacket, tacked onto the garment’s designer label, immediately triggered my memory of purchasing this suit. This Nipon suit was displayed at the front of a high-end retail store in Toronto called Lipton’s. Lipton’s was founded in 1950 by a Toronto couple, Evelyn and Marvin Goodman. By 1987, when I made my first purchase at Lipton’s Fairview Mall location in the suburbs of Toronto, the brand had become a retail clothing chain with 65 stores across Canada. From 1990-1991 the company was listed as one of the best companies to work for in the Financial Post’s “100 Best Companies to Work for in Canada.” Sadly, by 1995 the company filed for bankruptcy and was closed (“Evelyn Goodman”). This Nipon suit was my first and last purchase at Lipton’s in Toronto. I purchased this perfectly fitting suit and wore it twice that year. First in the summer for a formal outdoor occasion – I can’t recall if the invitation was for a personal, business or political event – and second, in the fall to an annual political fundraising dinner. This suit embodied all the aesthetic qualities I had come to love from the design cues I was getting from the world around me, including my style inspirations, Princess Diana, the Paris runway and popular culture.

Little did I know that while I was proudly wearing the “Albert Nipon” label, Mr. Albert Nipon himself was being released from 20 months in prison for tax fraud (Haynes)! Albert Nipon and his wife Pearl founded the label, in Philadelphia, PA in the 1950s. In 1984, before Mr. Nipon’s tax evasion schemes were underway, the couple was interviewed by Barbaralee Diamonstein, author of the book Fashion: The Inside Story. In this clip, Pearl, the head of design, introduces the Albert Nipon collection.

Above: Albert and Pearl Nipon interview with Barbaralee Diamonstein on the show Inside Fashion, 1984. Source: Diamonstein-Spielvogel, Barbaralee. “Inside Fashion: Albert and Pearl Nipon.” 1984.

As a consumer, I had no knowledge of the controversies surrounding the label and confidently wore my beautifully constructed power suit. Detail A below shows the construction of the jacket, with multiple panels that end in an inverted pleat creating the peplum style. Detail B is a close view of the fabric, 75% linen with 25% rayon. Perfect for a spring/summer outdoor event. The garment is fully lined, also making it perfect for an evening event in the fall/winter seasons. Detail C shows the meticulous construction. The lining mimics the same design detailing as the jacket it protects.

In keeping with the trends of the time, this power suit invokes status, with its angular shoulders and femininity, with the jacket nipped in at the waist creating a peplum hemline accentuating an hourglass figure and a simple body-hugging pencil skirt to the knee that reveals the legs while maintaining a level of modesty by fully covering the thighs. The simplicity of the ivory colour jacket with a black skirt is further enhanced by the bold black polka dot buttons on the jacket. Two columns of three buttons each, placed symmetrically on the torso make a bold statement. The jacket is double-breasted and yet only one of the six black buttons fastens.

For a young, aspiring career woman, the power suit of the ‘80s was a foundational building block in my professional career. I owned five power pieces in the ‘80s: the ivory and black Nipon suit, a wool knit Alfred Sung suit, a Jones New York silk jacket that I paired with skirts and slacks, an Alfred Sung navy wool blazer with very square shoulders and a single button closure placed low at the hip, and one prized red nautical theme Jones New York blazer with a blue velvet collar that also paired well with slacks and skirts.  I walked tall and proud in my power suits and separates. Reflecting on Merleau-Ponty’s work that says our bodies are the very means through which we come to know the world and articulate our sense of self (Negrin), I know that my embodied experience in those power suits changed my engagement with the world around me. When my body was dressed powerfully and confidently, my voice was not shy to speak up. Known as “enclothed cognition” (Adam and Galinsky), research has found that one’s attitudes and aptitudes shift when, as an example, one is wearing a doctor’s coat versus a lab coat. My ability to contribute powerfully and confidently is a skill I perfected in the ‘80s wearing my broad shouldered, commanding power suits.

I walked tall and proud in my power suits and separates. Reflecting on Merleau-Ponty’s work that says our bodies are the very means through which we come to know the world and articulate our sense of self (Negrin), I know that my embodied experience in those power suits changed my engagement with the world around me. When my body was dressed powerfully and confidently, my voice was not shy to speak up. Known as “enclothed cognition” (Adam and Galinsky), research has found that one’s attitudes and aptitudes shift when, as an example, one is wearing a doctor’s coat versus a lab coat. My ability to contribute powerfully and confidently is a skill I perfected in the ‘80s wearing my broad shouldered, commanding power suits.

Discussion Questions:

- What is today’s equivalent to the “power suit?” Is it the playground attire worn by IT geniuses changing the world or does the suit still have “power play” in the workplace?

- I almost sent my red blazer to the fabulous and talented Mr. Andew Antons of Thomas Tweed to have it converted to a custom messenger bag. What’s your vote? Shall I keep it in storage or ship it off to Andrew in Chicago?

Works Cited

Adam, Hajo, and Adam D. Galinsky. “Enclothed Cognition.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 48.4 (2012): 918–925. Web.

Bennett, Jane. “The Force of Things: Steps toward an Ecology of Matter.” Political Theory 32.3 (2004): 347–372. Web.

Cunningham, Patricia A. “Dressing for Success: The Re-Suiting of Corporate America in the 1970s.” Twentieth-Century American Fashion. Ed. Linda Welters and Patricia A Cunningham. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2008. 191–208. Web.

Cunningham, Patricia, Heather Mangine, and Andrwe Reilly. “Television and Fashion in the 1980s.” Twentieth-Century American Fashion. Ed. Linda Welters and Patricia A Cunningham. Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2008. 209–228. Web.

Diamonstein-Spielvogel, Barbaralee. Inside Fashion: Albert and Pearl Nipon. N.p., 1984. Film.

“Evelyn Goodman.” Ontario Jewish Archives. N.p., 2009. Web. 20 Feb. 2018.

Frisa, Maria Luisa, and Stefano Tonchi, eds. Excess: Fashion and the Underground in the ’80s. Fondazione Pitti Immagine Discovery, 2004. Print.

Haynes, Kevin. “Albert Nipon: Back in Charge.” Women’s Wear Daily 1987: 1. Print.

Hillman, Betty Luther. “‘The Clothes I Wear Help Me to Know My Own Power’: The Politics of Gender Presentation in the Era of Women’s Liberation.” Frontiers 34.2 (2013): 155–185. Web.

Mida, Ingrid, and Alexandra Kim. The Dress Detective: A Practical Guide to Object-Based Research in Fashion. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2015. Print.

Negrin, Llewellyn. “Maurice Meleau-Ponty: The Corporeal Experience of Fashion.” Thinking Through Fashion. Ed. Agnes Rocamora and Anneke Smelik. London, New York: I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd., 2016. 310. Print.

Riello, Giorgio. “The Object of Fashion: Methodological Approaches to the History of Fashion.” Journal of Aesthetics and Culture 3 (2012): 1–9. Web.

Stallybrass, Peter. “Marx’s Coat.” Border Fetishisms: Material Objects in Unstable Spaces. New York: Routledge, 1998. 183–207. Print.

Vogue. “Diana, Princess of Wales: A Life In Style.” Vogue. N.p., 2011. Web. 20 Feb. 2018.

WSGN. The 80s: Swagger & Spectacle. N.p., 2012. Print.

I love a good power suit. I am so happy that you explored this fascinating object.

You mentioned how John Molloy wrote Women’s Dress for Success book; and I had heard of this book before but never realized it was written by a male. How the times have (or have not?) changed that so many women would listen to what a man told them to wear. There is an interesting gender relationship in this, as well as obviously the power suit itself.

Your red blazer is INCREDIBLE. The boyish, school boy aesthetic in me would love a jacket like that! To answer your discussion, the object lover inside of me says do not touch that jacket: keep it as it is! You truly will change its meaning by converting it in to a bag. Now, some might see that as a good thing as it gives it a second life—every time you carry the bag you will think of when you wore it as a jacket, you will also create new memories with it, etc. But I say no! Keep it as is! It is such a cool treasure and preserve it as is. And honestly, if it still fits, you should totally still wear it!

I agree with you about the jacket Parker. It’s in near perfect shape, it would be a shame to destroy it. If it had a lot of wear and tear maybe, but it does not.

Yes, I’m grinding my teeth about the “men telling women” comment. I want to live to see the day men are no longer regulating and policing women’s clothing! Arrrgh!

It is so amazing to read how a woman was consciously choosing what to wear to be strong and start a career! I can sense from your post how the embodiment of your suit helped you embrace the business world in that period. I think that the definitions of power suits have changed. It can be either the suit or the hoodie plus jeans that the IT people wear. Although, I would bring a little Barthes to support me, as the signified would be changed signifier depending on the level of disruption these power people employ.

To your second question, do not touch it! You do not need to change it into a bag to still appreciate its history. I am all in favour of maintaining an object in its original form, as cited Bennett saying that material objects could evolve into trash, in this case is far too great a memory to end up transformed in another object.

Cecilia, you have me thinking about Barthes the signified and the signifier, this is a good example for me to learn from, thank you!

I agree, the jacket is pristine and it would be a shame to have it cut up. I will take it out of storage from time to time to tell its story!